|

The Last Manuscript of the Agnew

1568 Brían Ó Gnímh has no riches, other than his own manuscripts. Tonight he will depart Dunluce Castle with his soft, satin ceremonial cloak returned to him, his rod in hand. The call is made for Ollamh Flatha. Brían rehearses the opening line of ‘The tale of Guile’s daughter’, a tale he will tell as a metaphor for falling from grace and as an apology for seeking out a foreign patron. He closes his eyes to dismiss the images of Glenshesk, the bloodbath he witnessed two years ago, and he prays for the soul of Séamus Mac Dhòmhnaill, 6th chief of Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg, dead in captivity in his sixty-fifth year. All seemed lost then. He practises this tale, an ancient one in which a daughter must forfeit her duties of hospitality. She has no food to offer, just as Brían had no means for hospitality last year for four travelling princes, who supped on a meal as plain as that of their horses. So low had he fallen that he was no better than a common cainte. He must keep his status as ollamh, even if he has been a poor biatach — even if he has been a poor host. Never again will he return to such niggardly ways. Never again will his mind be so distorted by fear and war. Adversity has made him distressed, like the murdhucan sea bird, the siren he watched scream from his fortified tower in Ballygally. He must recover the name of scholars lost in the monasteries of Galloway, where his forefathers’ manuscripts burned. He must recover the name of Somhairle Buidhe Mac Domhnaill, descendant of Margery Byset and Eòin Mòr Tànaiste Mac Dhòmhnaill, whose alliance in 1399 gave Clan Donnell claim to the Glens of Antrim. Clan Dhòmhnaill needs Brían as much as Brían needs Clan Dhòmhnaill: he is no fool, but he will blind them all with poetry so that they believe his need is greater than theirs. Such is the art of diplomacy that Brían learned from his grandfather, Séann Ó Gnímh, who travelled Alba and Eireann seeking patronage and was set up by the O Neill family in Bally O Scullion, near Antrim. Such is the art of diplomacy that he learned from his father, An Fear Doircha, who travelled Alba agus Eireann seeking patronage and was set up by the MacDonnells at Priestland near Dunluce. Brían may have erred, but he knows his worth: he is at the top of his profession and his status will allow him to elevate that of the MacDonnells across all of Ulster. He will restore their name among the Gaels of Ulster, and for the sake of the MacDonnell reputation, he will call upon poetry to justify the murder of Séann O’Neill, the Earl of Tyrone. Brían closes his eyes and rhymes the names taught to him by his father. Brían, son of An Fear Doirche, son of Seaán, son of Cormac, son of Maol Mitnigh Óg, son of Maol Mithigh Mór, son of Gille Pádraig, son of Séann of Dun Fiodháin, son of Maol Muíre, son of Eóin. He says like a psalm. Brían will be married tonight to his true patrons of love and blood. He will chronicle the battles of Somhairle Buidhe Mac Domhnaill once again. He will provide him legal counsel and educate the youths, Domhnall Gorm and Alastair. He takes his rod and walks down the corridor to the throne room, accompanied by his entourage. Tonight he will sleep under his master’s roof. Tomorrow he will find a new home for Aibhlín and their infant son, who will be worthy of the name of a prince, Fear Flatha Mac Gnímh. 1611 Fear Flatha has been fasting to ready his body for the task. He lies in darkness on sheepskin after five days of nothing but water from the springs of Ben Moal Rhuarí. He has pledged to write a poem to Fear Dorcha, who is one of the Magennises of Iveagh, County Down. Only he will know it to be a lamentation on the loss of his father, the great Ó Gnímh, famed across the whole of Éireann agus Alba, who is now in a golden house. Only he will know it to be a lamentation for the death of his beloved wife, Catríona, in childbirth last year, and for his brothers, Séann, who died in battle, and Brían, who was not made to survive a fever brought by famine. Fear Flatha once resented his father’s calling. The lands bestowed to him at Cill Uachtair parish in the barony of Glenarm were not guaranteed when his patron was warring with the MacQuillans and the English. Fear Flatha’s father built up great flocks as the family moved from location to location, but such riches were of little consequence in war. There is no permanence in the allocation of poetic land. Poetry has brought his family little land and even less fortune, and now that threads of lore will no longer be spun, artistry and lyrics no longer woven, poetry is to be silenced, hidden in vaults. This is an imagined history of the Agnew sheriffs and Agnew bards of Kilwaughter, which is based on historical research. To keep reading this story, click 'read more.' You may also like my new novel: The Secret Diary of Stephanie Agnew.

0 Comments

“Perhaps the saddest incident comes from Ballygalley. An old woman, named Jane Parke, well-known to most of the residents of the neighbourhood, resided in a roughly-built cabin under the sea wall, a short distance on this side of the Halfway House. She lived principally by charity and recently was in receipt of Poor-Law Relief. Repeated warnings had been given her of the danger she incurred by continuing to reside in her tumble-down shanty in rough weather, but she was deaf to all advice, and now had met her death as the result of her obstinacy, her dwelling being completely wrecked and she either drowned by the heavy seas or was killed by the walls falling in on her.”

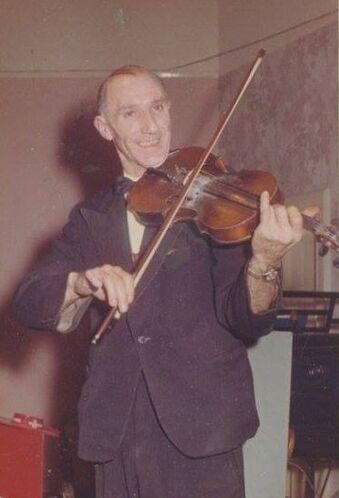

Larne Times, 29 December 1894 The following blog post was written in March 2020 after a walk around Ballygally trying to locate the position of Jean Park's home. Since writing it, a team of Jean Park enthusiasts have been in touch with more information, and this has become a truly enticing tale. I have highlighted anything new with an asterisk. Many thanks for your help.* I’m holding up the photograph of you, Jean Park — a face born of boulder, rock and shingle — but you did not emerge from these rocks; they say you emerged from the sea, a small baby found in a boat in her dead mother’s arms. Your face is contorted and twisted with age, older than your 71 years, but you had no time to prepare for any photographer. Did you know what you were doing when you agreed to squat down and look at the camera? Was the photograph taken the same year you died? A farewell. Something to make your legend real. I want to find a way to know where you resided. Was it on this spot, by Ballygally Head? I see the photographer, Robert John Welch, climbing down from the road past the seaweed drying out along the wall. I see him tip his hat and approach you. Today, you’re his golden find. He would record your name as Janet, but we know you as Jean, the common Ulster pronunciation of the name Jane. I hold up my mobile phone and see the rocks and the grassy bank and picture the telegraph pole in the photograph that was damaged the night that you were washed away. Above it are the mountains that stretch out along Path Head — misty in your photograph; exactly proportional to what I see through my iPhone’s eye. My brother sees Ballygally Castle behind you. (He sees castles where I see walls). The bank is ever-changing, as we witnessed with the carving of a large swathe of coast at Ballygally in a recent storm. Rocks come and go, but this seems like a good hiding place, an opportunistic spot; you would have been the first person to be seen as the tourists rounded the bend at Ballygally Head. This bay is the cold, dark edge of Ballygally. Did you pick it because you knew that no one would bother you here, that no authority would climb down and question you? It’s a cove below the head of a sleeping giant, whose face is handsome on approach from Larne or looking down from Sallagh, but here, up close, he’s stark and cold and covered in lichen. There was a time, not so long ago, when everyone had an aunt or uncle with a fiddle or melodeon. My great uncle Dan Hewitt was a well-known fiddler in the town of Larne and as a child, I delighted in the Aladdin's cave of melodeons, fiddles, saxophones and clarinets hidden underneath his sofa, not to mention the harmonica residing in his top pocket that appeared to have a way of conversing with children all by itself. When Dan played the fiddle on Radio Ulster in the 1980s, “us weans” took it as read that he must be the most famous man alive.

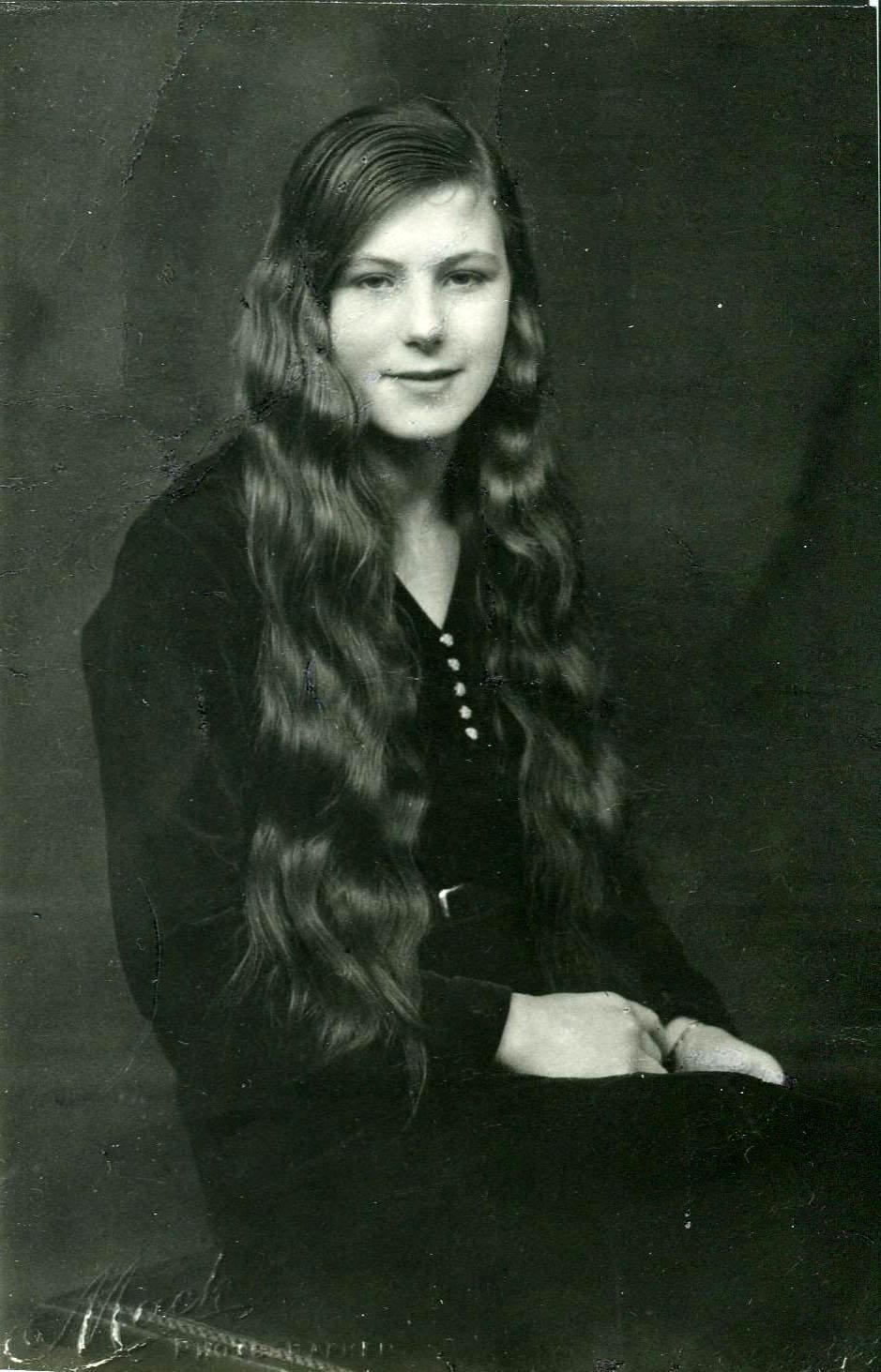

As I was writing ‘Irish Dancing: The Festival Story,’ I picked up bits and pieces about the history of music: the ancient harp and pipe traditions of Gaelic times; fiddle schools emerging all around Ulster during the 1830s and 1840s; the popularity of instruments as they became more affordable and the subsequent creation of bands comprising banjos, fiddles and melodeons - the “pop bands” of their time. The encroachment of jazz music and gramophone records lead to the belief that live music might die out all together, so in the 1920s Irish folk music, along with Irish folk dancing, was added to the syllabus of the musical festivals. Burning corks for eyeliner by the fire Two years ago I began to do some historical research for a new novel, which to be called Waterloo Road. I was able to draw from my own experiences, having grown up with great aunts and uncles who lived on the Waterloo Road, but when Barbra Cooke got in touch to tell me about her granny Martha Doey’s diary, the novel came to life in my mind. Barbra’s aunt Irene, Martha’s daughter, invited me to her home to learn more, and during that interview, I picked up the kind of detail that could not be found in a newspaper or a history book. I discovered a world in which women scrubbed their teeth with soot from the fire, painted their eyebrows with burnt cork and went hungry as rationing stretched from one world war to the next. A picture emerged in my mind, a hazy outline of an industrial area that only half exists today, the old red brick walls of the linen mill still standing on the Lower Waterloo Road; the unbridled noise of looms, smoke belching from chimneys and the giant damn for steeping flax near present day Kent Avenue all gone. The people who congregated at the factory corner outside Billy Boyd’s store were already known to me, as I’d spent so much of my childhood at that same corner buying sweets from Duddy’s or Sally’s shop, but I began to see my old aunts and uncles more clearly. I also started to understand the significance of the 12 foot high wall that separated the kitchen houses of the Waterloo Road from the big houses where the captains and doctors resided. I discovered the world of Little Ballymena, a quarter of Larne that has since lost the moniker for which it was once known. My great grandparents were among first generation to fill the kitchen houses on the Waterloo Road, Herbert Avenue and Newington Avenue in the late 1800s. They were farming people with “Broad Scotch” accents, an eclectic mix of every Protestant denomination; religious affiliations that were often determined by whichever church was providing handouts to the poor and needy. Such folk, alongside their Catholic friends, were all united in a love of whiskey, dancing and music. Martha Taylor’s diary is buoyant with the kind of language that comes from listening and yarning. The rhythm and phrasing her words echo conversations conducted over washing lines; tales whispered in queues when ships bearing bananas came into dock and stories formed in a world in which women talked for hours. I haven't attempted to reproduce any of Martha’s diary. The following words are merely notes with my own insights of a short but rich historical resource for the novel that came to be known as Dusty Bluebells. A life of serfdom Martha, who was born in 1917, begins the diary as a small child sitting on an army blanket in the back garden of number 15 Waterloo Road. The walls are thick with snow and she is content watching the robins hop along them. She is writing in the year 2001, her mind flooded with early memories. Martha’s peace on the army blanket is shattered when she hears soldiers marching. “Tramp, tramp, tramp,” she writes. She is a small child and she is afraid. A great military parade to welcome the soldiers home after Armistice is likely to have been the occasion. Brown’s Factory area is beset with unemployment in the 1920s as the linen trade goes into decline. Men are to be found on street corners lamenting the lack of work and gravitating towards socialism. Women, who are never far from hard work, continue to scrub laundry for a pittance, tend to cut knees, cook and clean.  Baby Jane Lyttle in 1914 Baby Jane Lyttle in 1914 My Great Aunt Jean McCullagh (nee Lyttle) was 104 this week. Happy birthday Jean! Jean is my granny Rossborough's sister. I interviewed her a couple of years ago when I was writing an historical novel and thought this would be a nice time to share what she told me. My mum is very fond of her aunt Jean. I always remember Jean sitting in the Murrayfield shopping centre when I was wee and my mum yarning to her for an eternity. Jean said that when she goes for medical appointments, the nurses sometimes take pictures of her. They also invariably ask her what the secret is to a long life. She tells them that she was reared on goats milk and that she had bacon, eggs and soda fresh from the griddle every morning. Jean's mother was Mary Lyttle (nee Gillen). She was from Ballysnod and lived there most of her days. Jean’s father was Samuel Lyttle, whose parents were from Maghera. Mary’s father was Patrick Gillen, who, like many people in the late 1800s, left these shores for America. He was forty at the time, and it is believed that he may have died before actually boarding the ship. His wife, Isabella Gillen, my great great granny, was therefore alone for most of her adult life. Jean loved visiting her Granny, Isabella. She too was from Ballysnod, but lived in a thatched cottage at Bank Quays near the Glynn. The house was on the opposite side to Howdens and located back from the road at the foot of a steep glen. Jean frequently ran down though the fields between Ballysnod and the Glynn with her siblings. They slept in an old settle bed filled with straw by the fire when they stayed over with their Granny Gillen. Jean recalls that her granny used to walk as far as Carrickfergus to sell eggs and to visit a relative. Childhood play for my granny’s siblings involved hoops and skipping ropes. The children also had free reign of Arnold's farm. Jean’s mother, Mary, rarely ventured beyond the end of the lane, but the world came to Mary’s door with people selling a variety of goods, not least needles, pins and thread, essential items for a talented seamstress. The fishman also came once a week, whilst Jean remembers an auld boy called Tinman, who sold the family tin cups and a tin teapot.  How did did our ancestors, the young and old of nineteenth century Ulster, foot it to the dance floor? The answer, if you're partial to Victorian literature, can be found in a recently republished novel called Orange Lily. May Crommelin’s novel, set in County Down in the 1870s, is well worth a read, but what caught my attention, as I made the last touches to my book on the history of Irish dancing, was the description of dancing, and in particular, the reference to Soldier's Joy, my 6 year-old daughter's favourite team dance. No slithery-slathery walzes!

‘Soldier’s Joy' is a popular team (country) dance in the festival tradition of Irish dancing, and the dance is a charming spectacle to behold as the children knock, knock, knock, clap clap clap and rolly polly polly to the music. However, in Orange Lily, the dance is a little more rustic. ‘Big Gilhourn,’ an affable farmer, who has taken a fancy to Orange Lily despite her unerring love for Tom, takes to the earthen floor of the barn like Michael Flatley, rejecting any notion of lilting to a modern dance: “None of your new slithery-slathery walzes for me. What I like best is to see a man get up and take the middle of the floor - and foot it there for a good hour!’ ‘The Soldier’s Joy’ for me, if I may make so bold as to ask that request.” Agnes McConnell (Close), was born in 1901 at 1 Railway Street, Ballymena. It isn't clear who taught Agnes McConnell to dance in the Irish style promoted by the Gaelic League, but Ballymena was a hub of traditional dancing in Agnes’ formative years, and the Protestant Hall in the 1910s and 1920s regularly accommodated Irish night festivities.

Agnes ran what the family called the “original and only dancing club in Ulster” in Railway Street from at least the late 1920s, if not earlier. Most of the McConnell siblings were involved in dancing, including Sam (b.1911), Fred (b.1915) and Pearl (b.1920). The children grew up in Harryville, a working class area of town that provided manpower for the local linen mill. Most of Agnes McConnell’s aunts and uncles worked at the mill — her mother, Margaret was a spinner and her father, David, a fitter. The McConnell family, who belonged to the Church of Ireland, would not have been part of the Gaelic League’s new dawn of saffron and green. Those Protestants involved in the Gaelic League revival of the early 1900s tended to be from middle class or aristocratic stock. Harryville was a unionist, working class and Protestant heartland where the voices were ‘broad Scotch’ and a Twelfth of July arch was decked out in in red, white and blue. The McConnells appear at the 1929 Ballymena festival as ‘The Shamrock team,’ featuring Miss Pearl McConnell, younger sister of Agnes. Their performance was noted by adjudicator, Mr Denis Cuffe, as the finest he’d seen in a life-time. In subsequent years, the McConnell dancers were entered into competitions under the name of ‘Miss McConnell’s school.’ Sally McCarley, who later taught her cousin, Sadie Bell (née Kernohan), was instructed by Agnes McConnell in the early 1930s. Sadie, who set up the Seven Towers School of Irish dancing in 1950, also The decommissioning of arms

Sean O’Togda complained in 1924 of the ignorance of youth as a result of the decline of the old dance masters. Mr O’Togda had a teacher of the traditional style who taught dancing to women in the following way: “To add grace and variety to the dance, he showed them how to dance with arms akimbo and to place the hands gracefully on the hips…He also showed the girls how to hold their skirts lightly at the side with thumb and index finger of both hands, and slightly and gracefully keep them out from the sides.” In a 1904 photograph of an Irish dancer, “Cassie” in Victorian attire at the Feis na Gleann, the dancer has both hands on her hips. Miss Patricia Mulholland, a Belfast dance mistress, who began teaching in the 1930s, was also an exponent of the use of arms. “As far as I was concerned, arms poker-rigid beneath an expressionless face had little attraction. I wanted to inject more feeling, and, in the process, let Irish dancing come into contact with the widest possible audience.” Arms were, however, discouraged by some dance teachers in the nineteenth century. Mr Trench, a dance master operating in the south of Ireland in the early 1800s instructed that arms should hang gracefully to the side. He actively discouraged the flinging of these limbs about, or flourishing them on the level with the head; an indication that the dancers either had a tendency to naturally liberate their limbs in ethereal motion, or that in some previous time, the arms had moved freely. Another reflection on pre-dance master times is this: “During the rapid exercise, Nancy occasionally clapped one hand on her well-developed hip.” The white collar scholars of the Gaelic League and the country dancers went head to head in a great national and nationalistic debate about what exactly Irish dancing was, and the Gaelic League turned to the south-west for inspiration, applying the Munster style found in areas of counties Kerry, Cork and Limerick to step dancing in the rest of the country. Dances were to be controlled, hip slapping and flings thereby excluded.  A dress from Leslie Baird's costume exhibition A dress from Leslie Baird's costume exhibition This week the sun was shining in Larne and the Orange Hall steps were ornate with dancers in emerald green, black, burgundy, royal blue, scarlet, navy blue and cerise. The festival was a positive experience made special by the charm of the dancers, the spirit of the musicians, the enthusiasm of the adjudicator, the generosity of visitors from across the province, the support from local people and the dedication of wee fairies who made it happen. There was also a strong sense of history. The lady at the door danced competitively in the same hall as far back as the 1930s, the pianist had danced as a toddler in a variety concert in Ballymena during the second world war, and the wee fairies on the stage and in the kitchen included grandmothers, mothers and daughters who have been dancing their whole lives. Few people realise is that Irish folk dancing, now primarily known as ‘festival dancing’ is a cross-community tradition. Even during the upheaval of ‘The Troubles,’ Catholics and Protestants continued to hold hands, literally and metaphorically, in towns like Belfast, Larne, Portadown, Ballymena, Ballymoney, Portstewart, Ballyclare and Bangor. Irish folk dancing, in fact, blossomed against the timbre of bullets and bombs. Catholics and Protestants in the Irish folk dancing tradition have been dancing together for for ninety years, but further back in time, the harvest homes, lintings, punch dances and Mayday festivities also provided opportunities for Catholics and Protestants to come together. Traditional Ulster social dances like ‘A Soldier’s Joy,’ ‘The Sweets of May’ and ‘The Three Tunes’ were danced by Protestants and Catholics before the term “Irish dancing” was invented. A story to warm the cockles of your heart:)  Photographer: Anne Montgomery Photographer: Anne Montgomery I was sick, sore and tired of the games that Harry and Gary played on the street. I was sick, sore and tired of BMXing, I was sick, sore and tired of A Teaming, I was sick, sore and tired of band sticking and I was sick, sore and tired of footballing. ‘I’m bored.’ I said to my mum. ‘How could you be bored? It’s summer. You’re off school. The street’s full of weans. Away out and play like the rest of them.’ ‘They only want to play on bikes and all. I’m bored of bikes and all.’ ‘Jenny’s on her own over there. Away and play with Jenny.’ My mum’s eyebrows were curved like question marks and she had a semicolon smile. She knew that I was not sick, sore and tired of Harry’s sister, Jenny. Jenny goes to the Andrew’s school of dancing at the Town Hall. Each Saturday, I’m there alone on the boy’s side of the hall. Jenny is there on the other side surrounded by thirty girls. It’s wile hard to be alone at dancing without stories birling through my mind. I do the three-hand reel with the girls. There’s a jellyfish of a girl on my left with arms and legs that wriggle in all the wrong directions. There’s a swan of a girl on my right with strong arms and graceful legs. The swan girl is Jenny |

ProseHistory & folkloreJean Park of Ballygally

Fiddles and Melodeons Martha Taylor's diary Jean McCullagh at 104 Ballymena & the McConnells Arms in Irish Dancing Catholics & Protestants in Irish dancing Dancing in Victorian Ulster Essays

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed