|

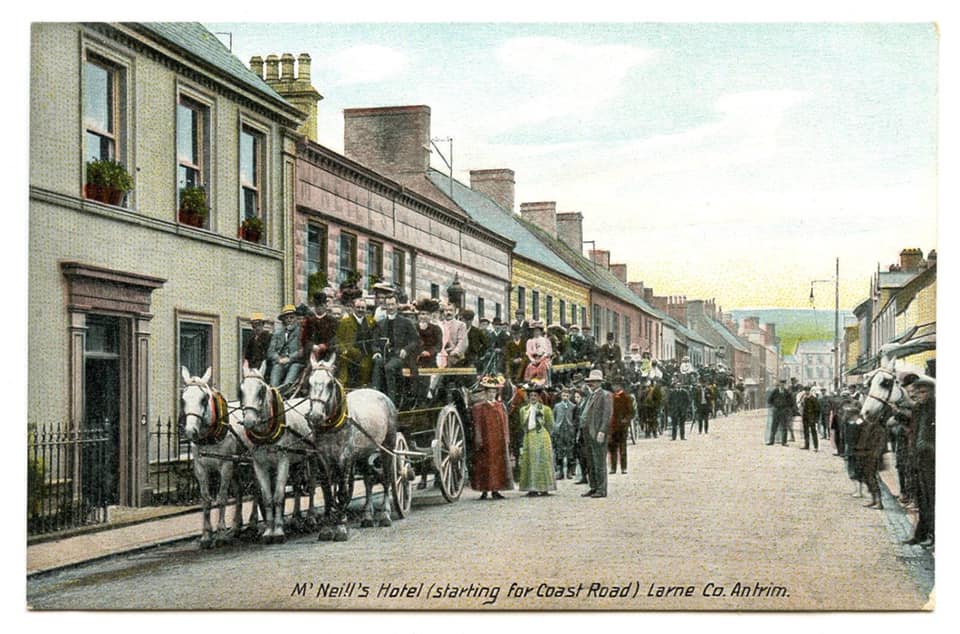

“Perhaps the saddest incident comes from Ballygalley. An old woman, named Jane Parke, well-known to most of the residents of the neighbourhood, resided in a roughly-built cabin under the sea wall, a short distance on this side of the Halfway House. She lived principally by charity and recently was in receipt of Poor-Law Relief. Repeated warnings had been given her of the danger she incurred by continuing to reside in her tumble-down shanty in rough weather, but she was deaf to all advice, and now had met her death as the result of her obstinacy, her dwelling being completely wrecked and she either drowned by the heavy seas or was killed by the walls falling in on her.” Larne Times, 29 December 1894 The following blog post was written in March 2020 after a walk around Ballygally trying to locate the position of Jean Park's home. Since writing it, a team of Jean Park enthusiasts have been in touch with more information, and this has become a truly enticing tale. I have highlighted anything new with an asterisk. Many thanks for your help.* I’m holding up the photograph of you, Jean Park — a face born of boulder, rock and shingle — but you did not emerge from these rocks; they say you emerged from the sea, a small baby found in a boat in her dead mother’s arms. Your face is contorted and twisted with age, older than your 71 years, but you had no time to prepare for any photographer. Did you know what you were doing when you agreed to squat down and look at the camera? Was the photograph taken the same year you died? A farewell. Something to make your legend real. I want to find a way to know where you resided. Was it on this spot, by Ballygally Head? I see the photographer, Robert John Welch, climbing down from the road past the seaweed drying out along the wall. I see him tip his hat and approach you. Today, you’re his golden find. He would record your name as Janet, but we know you as Jean, the common Ulster pronunciation of the name Jane. I hold up my mobile phone and see the rocks and the grassy bank and picture the telegraph pole in the photograph that was damaged the night that you were washed away. Above it are the mountains that stretch out along Path Head — misty in your photograph; exactly proportional to what I see through my iPhone’s eye. My brother sees Ballygally Castle behind you. (He sees castles where I see walls). The bank is ever-changing, as we witnessed with the carving of a large swathe of coast at Ballygally in a recent storm. Rocks come and go, but this seems like a good hiding place, an opportunistic spot; you would have been the first person to be seen as the tourists rounded the bend at Ballygally Head. This bay is the cold, dark edge of Ballygally. Did you pick it because you knew that no one would bother you here, that no authority would climb down and question you? It’s a cove below the head of a sleeping giant, whose face is handsome on approach from Larne or looking down from Sallagh, but here, up close, he’s stark and cold and covered in lichen. The labourers building the road must have felt his danger and left the road hair-pin narrow to end their travail. The head had a confused appearance, the Ordnance Survey recorded in 1835, “scene of some violent subterraneous commotion.” A poet, William Clarke Robinson, said it was "like lion crouched with threatening mien." How your fate and that of the poet would become entwined! This is the closest I’ve ever been to Carn Castle in Ballygally, the name given to the cluster of stones remaining from days of the Agnew/Ó Gnímh Gaelic chieftains and bards. Those stones, exposed to the elements for centuries on top of a towering basalt rock, have survived — a stronger pile than your little hovel. The Antrim Coast Road You would have been a child when William Bald and his men built the Antrim Coast Road. You would have been nine years old when it began to take shape, a teenager when it came through Ballygally. They call it the Causeway Coastal Road these days, the sole purpose being to reach the Giant’s Causeway — no journey for journey’s sake. In your time, thousands of tourists on jaunting cars made more regular stops. Your trade depended upon it. Marina Jane, William Clarke Robinson In his poem, 'Marina Jane' [*provided in full at the end of this blog], the poet said that a phantom ship slipped through the water on the night that you died. William Clarke Robinson would have been visiting his homeland when he penned his collection, his address Sea View Hotel in Glenarm at the time his book was published, in 1907 — around twelve years after you died. An international language scholar enraptured by your legend, Robinson scribed 29 verses of your story. He knew you, perhaps, though it is not clear if he was living in Ireland when you were residing at the shore. Whilst you live on as one of our leading legends, the man who wrote you into the annals of folklore has largely been forgotten. Fellow poet, Benmore, gave reflections of Dr. William Clarke Robinson’s life in the Larne Times on the occasion of his death in 1932, and he began by setting the scene of his social circles. Robinson moved with the celebrities of his time such as Francis Joseph Bigger, Ethna Cabery, Alice Milligan, Arthur Griffith, Eoin McNeilll and Douglas Hyde. Born in Deer Park, Glenarm, he was educated in Cairncastle by school master Patrick Magill before moving onto the Academical Institution Belfast, where he excelled at languages. He subsequently attended the University of Bonn in Germany and went on to live in Florence in Italy, winning academic fame in America, England, Germany and France. He penned many factual books on literary and linguistic themes, was a lecturer in Durham in England and a Professor of English Literature & History at Kenyon College in Ohio. He was active in Larne Literary & Debating Society in 1918 when he was resident of Carnlough; presumably he had moved home by then. He was also an orator of renown on the poetry of Robert Burns. Birth of Marina Jane The poet said you were found in a boat with your dead mother, who had just given birth to you, and this has become ingrained in our knowledge of you. Regardless of whether there is any morsel of truth in the tale, I wonder was your mother, too, born of boulder, rock and shingle? You survived. She made sure of that. That was 1823, the Irish Rebellion in living memory for the people of Ballygally in the parish of Cairncastle in the barony of Upper Glenarm. The village was not a village, but a townland of farms then, dominated by descendants of Scottish planters, mainly Presbyterians from Scotland. The parish covered a wide area from the shore to the hills, with 2,600 inhabitants — farmers prone to whiskey and dancing. “The general style of the houses in this parish is much superior to that of the neighbouring parishes,” Ordnance Survey writer James Boyle wrote in the 1830s. You were said to have a foreign look about you. In 1823, slavery was abolished in Chile, British convicts were transported to Australia, Portuguese rule ended in Brazil, France invaded Spain and a slave rebellion took place in British Guiana. Your mother could have come to occupy a little rowing boat cast down from a great ship from a distant shore, or you could have floated down from some nearby Scottish Isle, the Isle of Man — Rathlin even. The truth is that we don’t know. We think you look foreign, but it’s hard to tell when the ravages of time and wind are marked on your face. You could have been born anywhere. A Coastguard's Daughter The poet’s story has been adopted as the truth about you, Jean, and although it was written by a great scholar, I wonder how much of it is poetry and how much is fact. He said you were adopted by a coastguard, and this is plausible; Ballygally Castle served as a coastguard station and smugglers were still active when you were a child. At least four people were coastguards in the village in 1851, 28 years after your arrival, the year that the poet was born, and I have wondered, whilst searching for your maiden name if one of them was your adopted father. There were no Parks among those coastguard men. The poet said that you “nothing lacked.” As I think about you positioned in front of your cottage, ragged and worn, I wonder if this was a constant throughout your life; even as you had nothing, you nothing lacked. It’s a serene sort of thought this Sunday as the life we all know is about to go out in a storm. He said you married a farmer and a sailor and he named that sailor Park. *There is a good chance that Park was Jean's maiden name. I want to dally a while and see your childhood more clearly. The coastguard, if he existed, could not have raised you alone. Presumably a woman was involved. You would have been educated to elementary standard, no doubt, for the people of the parish of Cairncastle had a thirst for education; there were plenty of schools for every denomination. David Manson was born in the same parish one hundred years before you; he was a pioneering school master, whose story is as fascinating as your own. It comes with the territory in the parish of Cairncastle, what with a sailor being washed up in the Spanish Armada, supposedly giving seed to a beautiful tree that adorns St. Patrick’s Church yard up the hill. *[The tree referenced here blew over a few months after this was written.] Ballytober I searched through every Jane living in Ballygally in 1851 of twenty-eight years of age and could not find you. You could have been married by that time. *Both Jean's inquest and death certificate marked her as widow. It is likely that she married after 1851 and that her married name was McGill/Magill. I found one family of Parks in your area in 1851 in Ballytober, a townland situated in the countryside behind Drains, a bay named after the blackthorn and one that is a good brisk walk from here. In House 23 lived a farmer, Mr James Park, aged 38. His wife was called Margaret Park and was 26, around two years younger than you would have been at that time. There were two babies, Jane Park, aged two and a three-month old, Mary Eliza, as well as two servants. There had also been a Jane Park, mother of James Park, who died of natural causes in 1850 — at the end of the Great Famine. Another Jane Park, sister of James, died of consumption in 1842. The Park family of Ballytober townland may or may not have been connected to you, but seeing the family’s names in print gave me an idea of what your life might have looked like before you fell on hard times, and although there is no suggestion of babies in the poem by William Clarke Robinson, I found myself wondering if you had maybe lost at least one child, as was common at that time. Could it have been for the love of your husband alone that you took yourself to this shore, as the poet believed, or was some deeper part of you set adrift? *See below new details about Jane's children. The Famine Years The poem skips ahead from the merriment of an old country wedding with dancing, feasting and bonfires — nothing lacking yet again — to that fateful time when your husband went away, and what I’d ask you if you were sitting here beside me on this stony beach is — when did all this happen? Ballygally was not wholly dependent on the potato crop in the 1840s. There was a variety of other staples, such as beans and barley, some meat and also the shellfish and seafood so close at hand. You lived through the Great Famine of 1845-1849 in your youth, and so it is often assumed that you lost your livelihood at that point. It is certain that Larne Workhouse burgeoned with hungry labourers from the countryside during the Great Famine, but it is also possible that you survived the catastrophe without losing your home, that the event of your husband’s absence came later — if at all. *Jean started her family after the Great Famine. It is still unclear when Jean lost her husband, if she did, but the inquest into her death reveals that she had been living on the shore for 7 years. Tourism It is known that your trade was selling dulse to the tourists who came up the coast every day from Larne — a tourist resort in your day and for many decades after. Your trade is written on the photograph taken of you by Robert John Welch. It’s part of the legend that is easier to believe. News of your death was reported to the Lancashire tourists who came on package holidays each summer. They knew you. The dulse selling sets you apart as an entrepreneurial pauper cashing in on the tourist trade in much the same way that Henry McNeill cashed in on the Antrim Coast Road and the postal route to build up his package holiday empire. *That Jean sold dulse is backed up by the inquest into her death. She sold dulse in the summer and relied on poor relief in the winter. I Mystery of the Deep The poet says that you had some sort of vision about your husband’s fate, a presentiment of his “mystery of the deep,” a bit like standing here now at the edge of something, knowing that events in the coming days will mark the end of one life and the birth of a new one. Nature will have time to heal as the cars and planes are halted, but we will know some kind of hardship to pay for what has passed. Many people tried to help you when your sailor went away, according to the poet. They tried to keep your farm going, but you let it fall to “waste and weeds.” The newspaper recordings suggest that you were given chances on the eve of your death that you didn’t take. You dictated your own fate. *Jean was offered at least one other opportunity to have a roof over her head, as described by her daughter at the inquest. We know the rest of the poem to be true. You did build a hut here below the posting track, and although the shore changes dramatically every day, such loose stones remain within reach, as do the long, heavy whips of kelp stalk at my feet that are as tough as wood. The poet tells us you had a wee dog called Brinie and that Brinie and her pups went on to survive when you refused heed warnings about the storm and stayed down by the shore. Of course, there is no evidence that you had pups at all. * That the poet knew about pups and not Jean's child/children perhaps suggests that he didn't meet her or know her and was reliant on his imagination. Also his assumption that her married name was Park is unlikely to be true. A Hurricane to remember I think of my great granny Isabella Gillen when I think of you. Isabella was from Ballysnod and raised her family there, up high, at a distance from the shore, but she lived out her days in a wee thatched house near the railway line on Bank Road between Larne and the Glynn. She too would have felt the full force of the hurricane on the night of 21 December 1894. Few thatched roofs survived after six to seven hours of wind blowing with the strength of a tornado. The storm reached its height between 2.30am 3.00am and Isabella Gillen must have cried with relief when it was all over, an event that continued to cast a shadow over Larne throughout Christmastide. In the centre of the town, slates and chimney pots came crashing down, fountains were blown over, trees born up on the Bank Road — even the ducks on Larne Lough struggled to make good their escape. Telegraphic communication was “demoralised.” On the eve of another storm, we can’t afford to be demoralised, but we know what lies ahead, our presentiment flashing up on the screen in Italy and Spain every minute of the day. The poet wrote — inaccurately — that all trace of you was gone, but the Belfast News Letter reported on 25 December 1894: “On Saturday afternoon the dead body of the old woman was picked up near Ballygally and removed to the boathouse at the coastguard station, and an urgent request will probably be held today.” You made your way back to your adopted home, Jean, and then you were buried. On Saturday 22 December the Blackburn Standard reported that the telegraph wires were destroyed, the poles of the electric light company were damaged, that ships were beached at Millbay, boats were wrecked, bathing boxes in Larne ripped up and the stage at the promenade damaged. Elm trees were plucked up by the roots, the Congregational Church stripped of its steeple and then there’s you, Jane Park of Ballygally, a pauper’s death reported in England. Your death certificate cites you were a widow, aged 71, who died on 21 December 1894, a labourer drowned during the hurricane of that same day; the latter information provided by JJ. Adam. Your story is the dream of writers and artists inspired not by great rulers and patriotic heroes, but by men and women born of boulder, rock and shingle, those who defy convention and live at the harsh, cold edge of something until it’s time for them to go back home. *The missing piece Jean Park, what makes you ever more mysterious is that you had a daughter. At your inquest, Dr. John McKillen reported that an effort had been made to remove you from your hut. The Poor Law Guardians declared it unfit for habitation. He stated, "The Guardians so far as I am aware took no action." Perhaps they did take action and you took no heed of them. The doctor was satisfied that your death was down to drowning. Your daughter was also called Jane (Jeanie). It is through Jeanie that we have some clues to your true story. Jeanie was born in 1859, when you were approximately 26. She was living on Mill Lane when you died and she confirmed that you gathered seaweed during the summer and then lived off poor relief in the winter. She said you "lived on charity," although whether this means that you lived in the poor house in winter is not clear. You had grandchildren, including another little Jeanie, born in 1887, six years after your daughter was married — the same year that you went to live at the shore. Your daughter said, "I tried often to get her to leave and live with me." So, why didn't you go? Did you value your independence? Or, did you decide that living in a hut in a wild paradise was preferable to living in a bustling town underneath the smoke of a mill? Your daughter said that three weeks prior to your death you were well. So, it seems she was on good enough terms to visit you, and if she told the truth, she also cared about you: "The hut was so near the sea that I was anxious for my mother to leave." Your daughter also seemed to know your habits: "She took off all her clothes when going to bed." You were found naked, although the clothes in the picture look like they are part of your skin. William Wilkins of the Coastguard Station (now the Ballygally Castle Hotel) said that you lived near the Coastguard Station. This would place your hovel close to the boathouse, which still stands today. He says you were found dead by the boathouse and reported that there was nothing of the hut remaining. He knew you well and provided an insight into your personality. He said you were quiet. So, we know that you were quiet, stubborn, tough and entrepreneurial. No wonder women are intrigued by you. Descendants Well, Jean, your family live on today. Four of your Armstrong grandchildren were born while you were alive. There was William, Jeanie, Nancy/Agnes, Andrew and then after your death, John Gordon Holmes. The name Jeanie stands out to me because your daughter was proud enough of you to name her daughter after you. Your daughter's name reveals a little more about you. Two official documents — the inquest and your death certificate — mention that you were married; it has been assumed by many, including the poet, that Park was your married name. However, when your daughter was married on 23rd November 1881 in the Cairncastle, Church of Ireland, to Andrew Armstrong, her maiden name was Magill. Jeanie was "full age" (21) on her wedding day. Her father, John Magill, a labourer, is named on the marriage certificate, which he signed. Your husband was John and he was still alive in 1881, long after the famine. There was a John Magill who died in 1882, aged 60. It is possible that this was your husband. Your daughter, Jeanie Armstrong (née Magill), was a servant when she married Andrew Armstrong, who was a labourer, and it states on her wedding certificate that she was from Ballytober near Drains Bay. Could there have been a connection between your daughter and the Park family of Ballytober?Was she their servant? There is also something curious about your daughter and her relationship with the name Park. As I said, on her wedding certificate, her maiden name is Magill. However, on her son's birth certificate, her maiden name is Park. This son, Andrew James Armstrong, was born on 13 November 1893. The same document saw a correction appear on 19 August 1929, 36 years later. Your daughter, Jeanie, by then seventy, went along to the registrar's office and asked for the name Park to be corrected to Magill on the birth certificate. Could it be that Park was her middle name and that you, for whatever reason, were known exclusively by your maiden name? When I saw a burial notice from St. Patrick's Church of Ireland in Cairncastle concerning a John Magill, a bachelor, who died in November 1894, only weeks before your death, I became curious. He was 48 years-old when he died of nephritus — an inflammation of kidneys. What caught my eye was that he lived in Ballytober, the small townland where your daughter, Jeanie, lived. This would mean he was born in 1846. I wonder was he a relation too. (Could he have been your son?) There was also a James (77) and Jenny Park (60) living in Ballytober in 1851 at house 12 — another potential link. They would have been old enough to be your parents. Is it possible that you were, in fact, born locally? My tale ends ends with another Jeanie Park, your great great grand-daughter. This Jeanie Park lives in America and is now called Jeanie Clarke. (Coincidentally, I created a wild woman who lived on the shore in Dusty Bluebells and called her Mary Beth Clarke — to rhyme with Park, a little nod to Jean Park.) Well, Jean, if you're still listening, and by now you must be both tired reading and smiling from the grave, Jeanie Clark (née Park) is the grand-daughter of Jeanie Armstrong, your grandchild, the one born the year that you moved to the shore. Jeanie Clark was told about you, that you had drowned in Ireland, and this information was passed down through five generations. You'll be glad to know that your daughter, Jeanie, had many friends in Scotland. This information was provided by your great granddaughter, Margaret, the one responsible for bringing the Park name back to the family through marriage. (She was Graham to her maiden name and lived in America). She said Jeanie Armstrong used to sit and gossip and drink strong tea, served in earthenware bowls and that she and her family were of the Orange tradition, as would be expected of any Protestant moving to Scotland in the early 1900s. Your daughter thought that mirrors were sinful and made you full of vanity. I wonder if she learned that from you, a woman who forfeited all vanity and material possessions to live a dangerous, cold and wild existence in the winter of her life. Jean, you remain a mystery and I hope you can forgive me for stealing a little bit of your mystery for my novel, Dusty Bluebells. The full poem, Marina Jane, can be found below in all its romantic glory along with family photographs. Thank you to Andrew King, Jenny Brennan, Jeanie Clarke and all those who have helped put this story together. Dusty Bluebells Historical novel. A musical hearty and spiritual family mystery set in an Irish seaside town. "Pithy with Ulster Scots, old rhymes, cures and sayings, there is a sense of magic to it all" (The Irish Times). Click here to buy. Snugville Street Contemporary novel. "An enjoyable coming-of-age tale with a Belfast twist" (The Irish Times) Click here to buy A Belfast Tale Contemporary novel. “Uniquely, authentically and enjoyably Belfast" (Tony Macaulay, author of Paperboy.) Click here to buy. Irish Dancing: The festival story A history of dancing in Ulster with a focus on the festival tradition of Irish Dancing. Click here to buy. Children of Latharna Stories for big weans and wee weans. "Lyrical and nostalgic; wistful and humorous," Ian Andrew, author. Click here to start reading for free Marina Jane: A Tale of Ballygally Bay W. Clarke Robinson Along the sounding Ballygally Bay, One summer morn there drifted in a boat, With mother dead, and babe scarce aged a day Beside her, but no other thing of note, To tell from whence they came, or from what wreck; "Marina Jane," this babe a coastguard named, And bore it home, where it should nothing lack, And where it grew a maiden fair and famed. A lusty sailor, Parke, with farm of land, With foreign ways, and gifts above his means, Then woo'd and wed this changeling of the strand, And blithe and gay were all the wedding scenes: The church was filled with girls and farmers' sons, And some took rights to kiss the fair new-bride-- With cheering, dancing, feasting, firing guns, And burning bonfire barrels at eventide. The sailor settled on his native lea, With frequent voyages to pay his rent; And thus for years he ploughed the land and sea, In health and happiness and sweet content. But once when absent on a voyage strange, A shadowy dream on Jeanie seem' d to fall: That ne'er again across the ocean's range Would he return or answer to her call. And woman's dreams about the things they love Are often times divine presentiments; They leap our logic, and all wireness move Quick to the point and goal of their intents. The wives of Ceasar, Pilate, William Tell, Dreamed just like Jeanie of their husbands' fate; And other wives have dreamed what ne'er befel To any husbands, either soon or late! His vessel, never reaching port, was lost, And perished as “a mystery of the deep”; Yet Jeanie's wistful eye still watched the coast, And oft would see him landing in her sleep. For still the inextinguishable hope Of her dear sailor's final coming home, Would buoy her up 'gainst all her fears to cope, And lead her daily on the beach to roam. The farm, uncared for, went to waste and weeds, Though oft a friendly neighbour lent his plough. Or some came late to reap, or sow her seeds, Or went to market with her pigs or cow. But landlords' bailiffs broke at length the latch, And cast her from the cot and quenched her fire, Nailed up the door and windows, and the thatch Tore off, and left her in the road and mire. Then to be free of landlords, on the beach She built a hut below the posting track, With such loose stones as lay within her reach, And roof'd with driftwood, grass, and wither'd wrack. And there, without a window or a door, She squatted rentless by the windy sea, And daily gathered limpets on the shore, With one wise little dog for company. Her doggie, Brinie, never left her side; That wise philosopher, with soft black eyes, Could read her mind and every change of tide, And all the varying signs of seas and skies. And this good Brinie brought new life and cheer To her in that lone weather-beaten hut; Hoped its four young puppies there to rear, And pleased her with the capers which they cut. The warm wee things lay curl'd upon the bed, Their noses cold as any balls of snow-- Men's knees, dogs' noses, and girls' hands, 'tis said, Are always cold, their warm hearts thus to show. This sea-born Jeanie lived among the stones, Like the sweet dulse or clinging limpet shell; The summer waves, the wintry breakers' moans Alike to her; she could not think nor tell. That all these seeming-simple forces have A power latent like a lion mild, And may anon excite themselves and rave And rend the thing they play'd with as a child. There came a day suspicious-extra fine! With a red sunset o'er the winter sea; And black clouds gathering on the ocean line, And beasts and birds all drifting to the lee. And then the trumpets of the sea and sky Proclaim aloud the lowering storm has come ; The winds and waves in fierce contention vie, And nature roars while man and beast are dumb. The waves tumultuous leap upon the land-- Their white teeth reddened with the bleeding earth, And stones and rocks, as by a demon's hand; Are heav'd around poor Jeanie's hut and hearth. A neighbour came to take her from the shed, But left it fearful since she would not go: “Her trusty sailor might that night come dead, And she not there her helping hand to show!” And her brave Brinie looked into her face, Then looked again upon the rising sea, And pulled her tattered dress towards the place Of exit while she still could safely flee. It could not take her; so it turned and took One little puppy in its gentle grip, And bore it inland to a sheltered nook And then another on a "swimming trip," Till all the four wee sightless, whining things Were safe and silent in their second home, Meantime the surging water saps and flings Poor Jeanie's dwelling level with the foam! Some said a phantom ship that night went by, Some thought they saw a boat along the shore, Some heard a voice from out the billows cry, And then all vanish'd with the ocean's roar! Next morn they sought ner in the hovel poor But sign of hut or hovel there was none! Poor Brinie and her brood were all secure, But every trace of Jeanie Parke was gone! The hungry sea had claimed what first it gave; She doubtless joined him after severance long; And o'er them both, beyond the broken wave, The sea wind sings its ever plaintive song.

12 Comments

Brendan Davis

10/1/2021 13:43:56

Enjoyed and found very interesting. Thank you

Reply

Angeline King

25/1/2021 18:33:02

Thanks Brendan! Glad you enjoyed it!

Reply

Anne McCusker

12/1/2021 15:36:36

Lovely to see Jane remembered. Thank you for all the extra info. Very interesting.

Reply

Angeline King

25/1/2021 18:33:21

Thanks Anne!

Reply

Peadar Murphy

17/1/2021 18:27:58

Very interesting and nicely put together Angeline.

Reply

David McMaster

16/2/2021 01:11:04

I remember the storm in 1959, I was eleven years old at the time. The winds were ferocious, whipping and enraging the sea. I had no knowledge of this lady, Jean, perishing in the waves at Ballygally. Thankyou for the insightful knowledge, imparted in the story and the addition of an epic poem

Reply

Laurence McAuley

16/2/2021 13:24:35

Thanks Angeline for all the extra info...I’ve been interested in Jean for many years as my ancestors would have known her well...my g/g/g/g grandfather John McAuley lived as a tenant farmer in the old farmhouse opposite todays back entrance to Ballygally carpark...one of the Coastguards mentioned John Colton married his granddaughter!

Reply

David Hume

17/2/2021 20:33:11

Fantastic piece Angeline, and to complete with rediscovery of the family of Marina Jane was outstanding.

Reply

And king

18/2/2021 03:57:48

Just found out her funeral was in Ballygally and also at the ‘Armada Tree church’ - St.Patricks Church of Ireland. I’m assuming she is buried there. Henry McNeill was actually a guardian for the workhouse. ( He often had a Workhouse Brass Band on the sea excursions he organised.). I don’t think she even went to live in the workhouse in the winter - she died on December the 21st. She lived off the charity of the local Ballygally people and they all knew her. During the storm, a house in Ballyboley actually completely blew away. Could she have married a Parke first ? He maybe died and then she had a child with John Magill. It’s is very strange that there is no more mention of John Magill after 1881. Perhaps he did go to sea and never returned. It does mention in the inquest that the landlord wanted her out , although I’m not sure if this is the hut or her previous house. There must have been some reason she wanted to live at the hut. It’s actually hard to think of a more inhospitable place to live. Maybe she wanted to be close to the safety of the coastguard as she was possibly brought up in the castle and felt safe in Ballygally. Maybe there was a lot of facts in the poets story, as he wrote It in 1907, only 13 years after the incident. Every person he talked to in the area, when researching about her, probably personally knew her. Henry McNeill also owned the Seaview hotel, Glenarm.

Reply

Jean P. Clark

20/2/2021 23:18:42

Dear Angeline, I just lost my email I had written. Maybe I made it too long. By now your know I have been in touch with your brother Andy. He has been so kind to send me your story about my great, great, grandmother Jane (Jeanie) Park. I was told by my mother years ago that she had drowned in the Irish Sea. I have shed tears over the rest of her story that you have written and wish to thank you. Under her page on "Family Search" I will write the rest of her story and tell how you wrote it and that you and Andy researched it. You will be read by many of her descendants. You are both so amazing. I ordered your book "Dusty Bluebells" off of Amazon this morning and will continue to follow you and the Renovation Generation. Thanks again, Jeanie

Reply

Heather Lea (Park) Johnson-Gornick

18/3/2023 14:35:42

She would have been my Great, Great, Great Grandmother. My Aunt Jeanie Park and her brother, my Father is Thomas Park. Thank you for a beautiful following on this heritage.

Reply

Angeline

19/10/2023 14:43:25

Hi Heather, so sorry that I’m only seeing this message now! It would be nice to say hello via email. My address is: [email protected]. Best wishes!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

ProseHistory & folkloreJean Park of Ballygally

Fiddles and Melodeons Martha Taylor's diary Jean McCullagh at 104 Ballymena & the McConnells Arms in Irish Dancing Catholics & Protestants in Irish dancing Dancing in Victorian Ulster Essays

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed