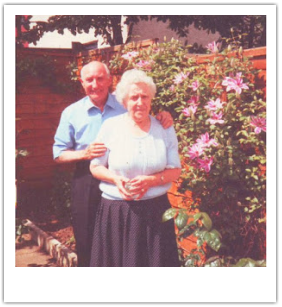

You peek your upturned nose through the letterbox, inhale the smothering scent of wee buns, and holler, ‘Naaaan!’ You wait. The birds are pecking at the bird box, the drizzle is dripping from the roses and the concrete steps shimmer like marble. You see a face at the window with hollow cheeks. It’s not quite your Aunt Nan, but she opens the door, puts her teeth back in, smiles and you feel rich. It’s Tuesday. The twin tubs are swivelling their hips — one for washing, one for rinsing. The buns are ready and Nan lifts them onto a cooling rack. She has eyes on the back of her head. Tut tut and a tap on the hand.

5 Comments

|

ProseHistory & folkloreJean Park of Ballygally

Fiddles and Melodeons Martha Taylor's diary Jean McCullagh at 104 Ballymena & the McConnells Arms in Irish Dancing Catholics & Protestants in Irish dancing Dancing in Victorian Ulster Essays

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed