|

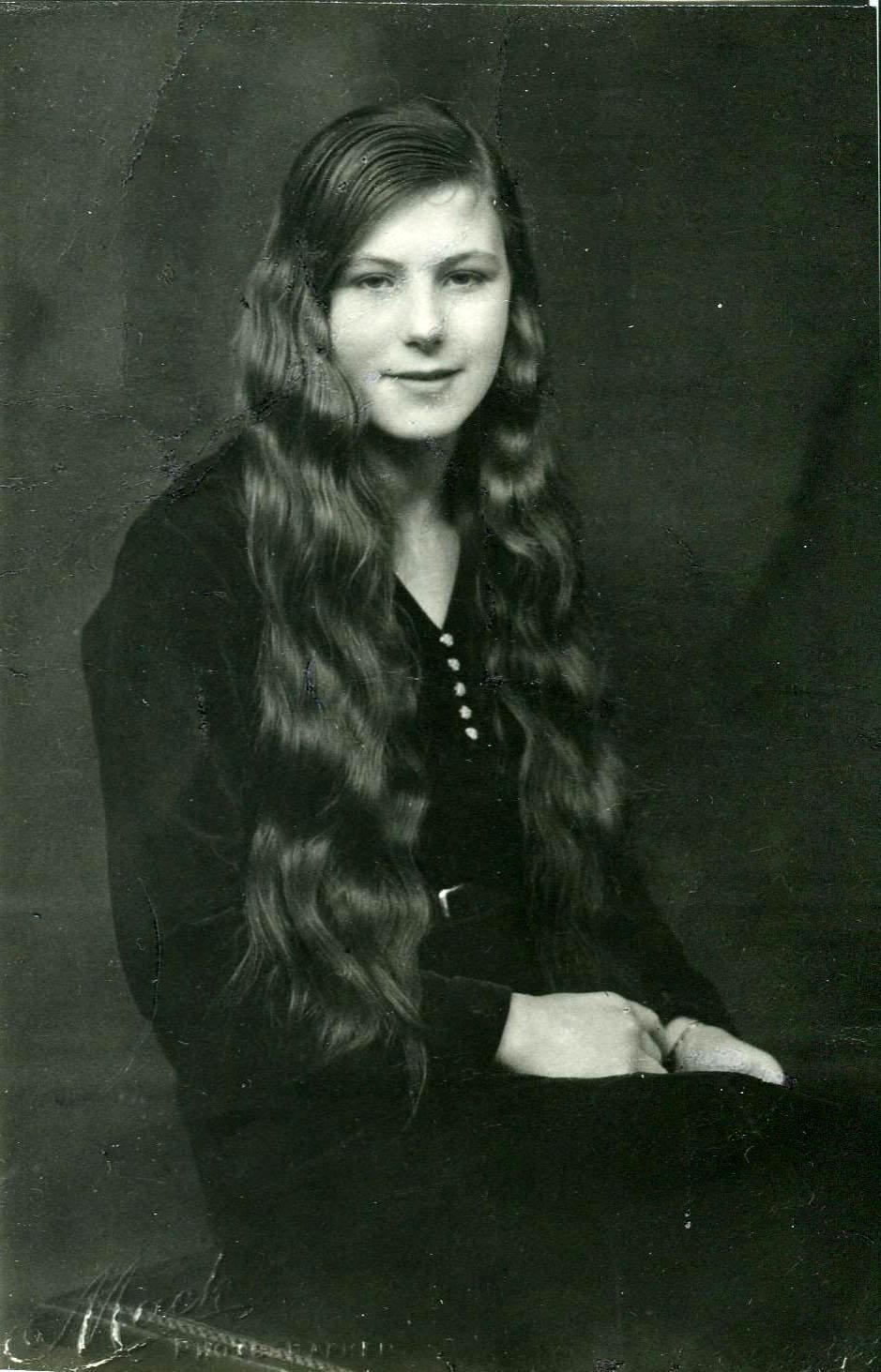

Burning corks for eyeliner by the fire Two years ago I began to do some historical research for a new novel, which to be called Waterloo Road. I was able to draw from my own experiences, having grown up with great aunts and uncles who lived on the Waterloo Road, but when Barbra Cooke got in touch to tell me about her granny Martha Doey’s diary, the novel came to life in my mind. Barbra’s aunt Irene, Martha’s daughter, invited me to her home to learn more, and during that interview, I picked up the kind of detail that could not be found in a newspaper or a history book. I discovered a world in which women scrubbed their teeth with soot from the fire, painted their eyebrows with burnt cork and went hungry as rationing stretched from one world war to the next. A picture emerged in my mind, a hazy outline of an industrial area that only half exists today, the old red brick walls of the linen mill still standing on the Lower Waterloo Road; the unbridled noise of looms, smoke belching from chimneys and the giant damn for steeping flax near present day Kent Avenue all gone. The people who congregated at the factory corner outside Billy Boyd’s store were already known to me, as I’d spent so much of my childhood at that same corner buying sweets from Duddy’s or Sally’s shop, but I began to see my old aunts and uncles more clearly. I also started to understand the significance of the 12 foot high wall that separated the kitchen houses of the Waterloo Road from the big houses where the captains and doctors resided. I discovered the world of Little Ballymena, a quarter of Larne that has since lost the moniker for which it was once known. My great grandparents were among first generation to fill the kitchen houses on the Waterloo Road, Herbert Avenue and Newington Avenue in the late 1800s. They were farming people with “Broad Scotch” accents, an eclectic mix of every Protestant denomination; religious affiliations that were often determined by whichever church was providing handouts to the poor and needy. Such folk, alongside their Catholic friends, were all united in a love of whiskey, dancing and music. Martha Taylor’s diary is buoyant with the kind of language that comes from listening and yarning. The rhythm and phrasing her words echo conversations conducted over washing lines; tales whispered in queues when ships bearing bananas came into dock and stories formed in a world in which women talked for hours. I haven't attempted to reproduce any of Martha’s diary. The following words are merely notes with my own insights of a short but rich historical resource for the novel that came to be known as Dusty Bluebells. A life of serfdom Martha, who was born in 1917, begins the diary as a small child sitting on an army blanket in the back garden of number 15 Waterloo Road. The walls are thick with snow and she is content watching the robins hop along them. She is writing in the year 2001, her mind flooded with early memories. Martha’s peace on the army blanket is shattered when she hears soldiers marching. “Tramp, tramp, tramp,” she writes. She is a small child and she is afraid. A great military parade to welcome the soldiers home after Armistice is likely to have been the occasion. Brown’s Factory area is beset with unemployment in the 1920s as the linen trade goes into decline. Men are to be found on street corners lamenting the lack of work and gravitating towards socialism. Women, who are never far from hard work, continue to scrub laundry for a pittance, tend to cut knees, cook and clean.

2 Comments

|

ProseHistory & folkloreJean Park of Ballygally

Fiddles and Melodeons Martha Taylor's diary Jean McCullagh at 104 Ballymena & the McConnells Arms in Irish Dancing Catholics & Protestants in Irish dancing Dancing in Victorian Ulster Essays

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed