|

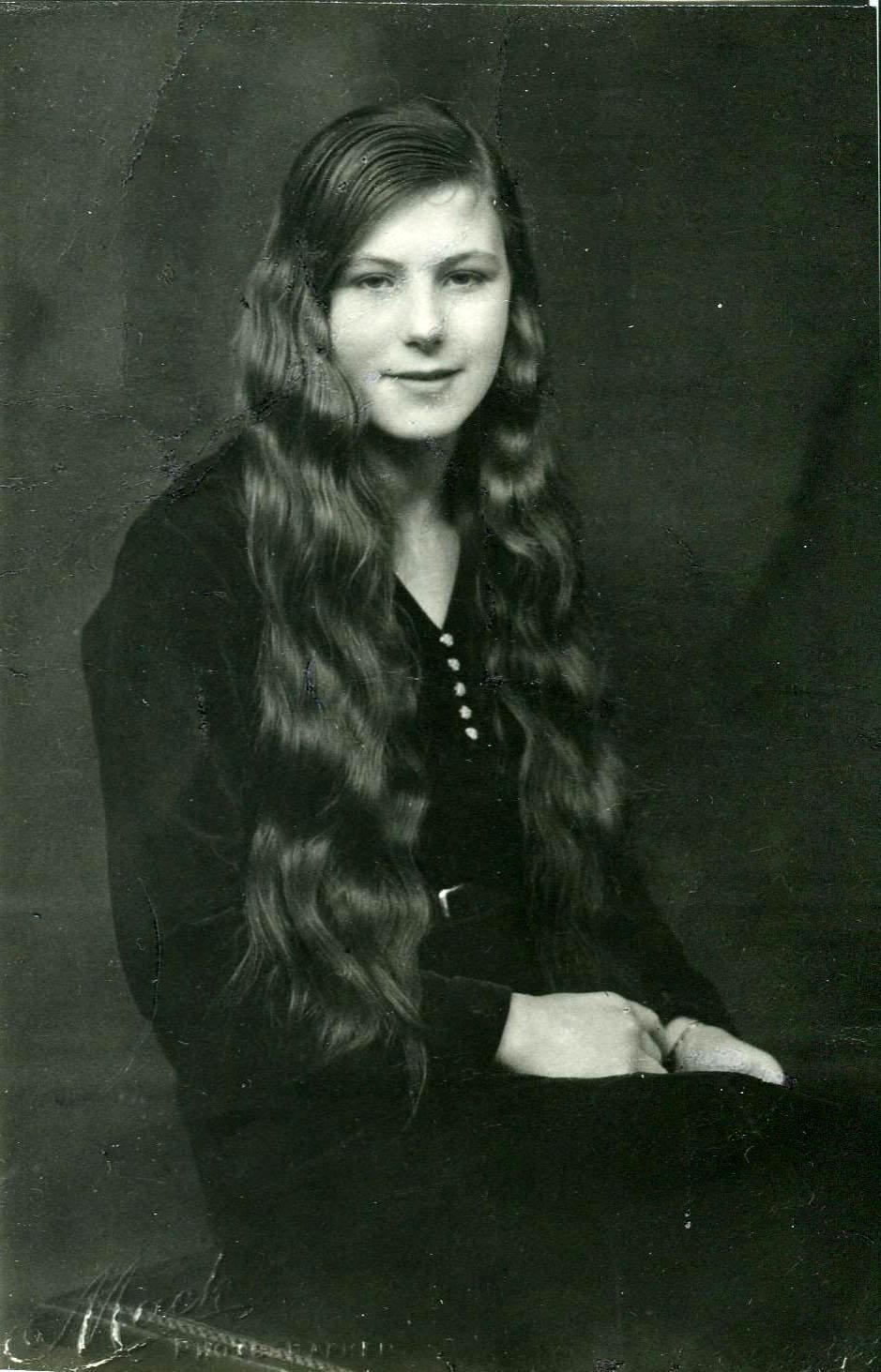

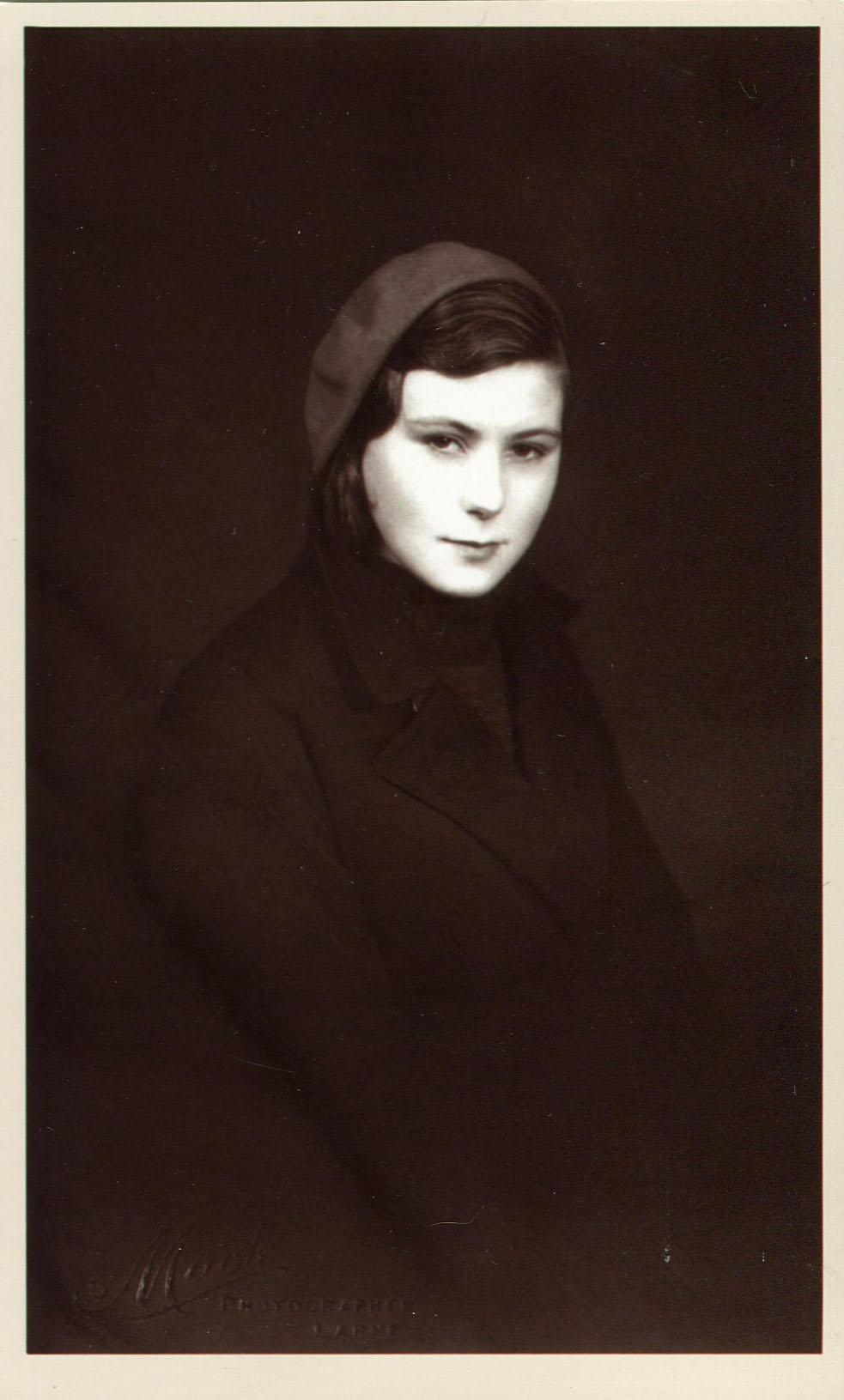

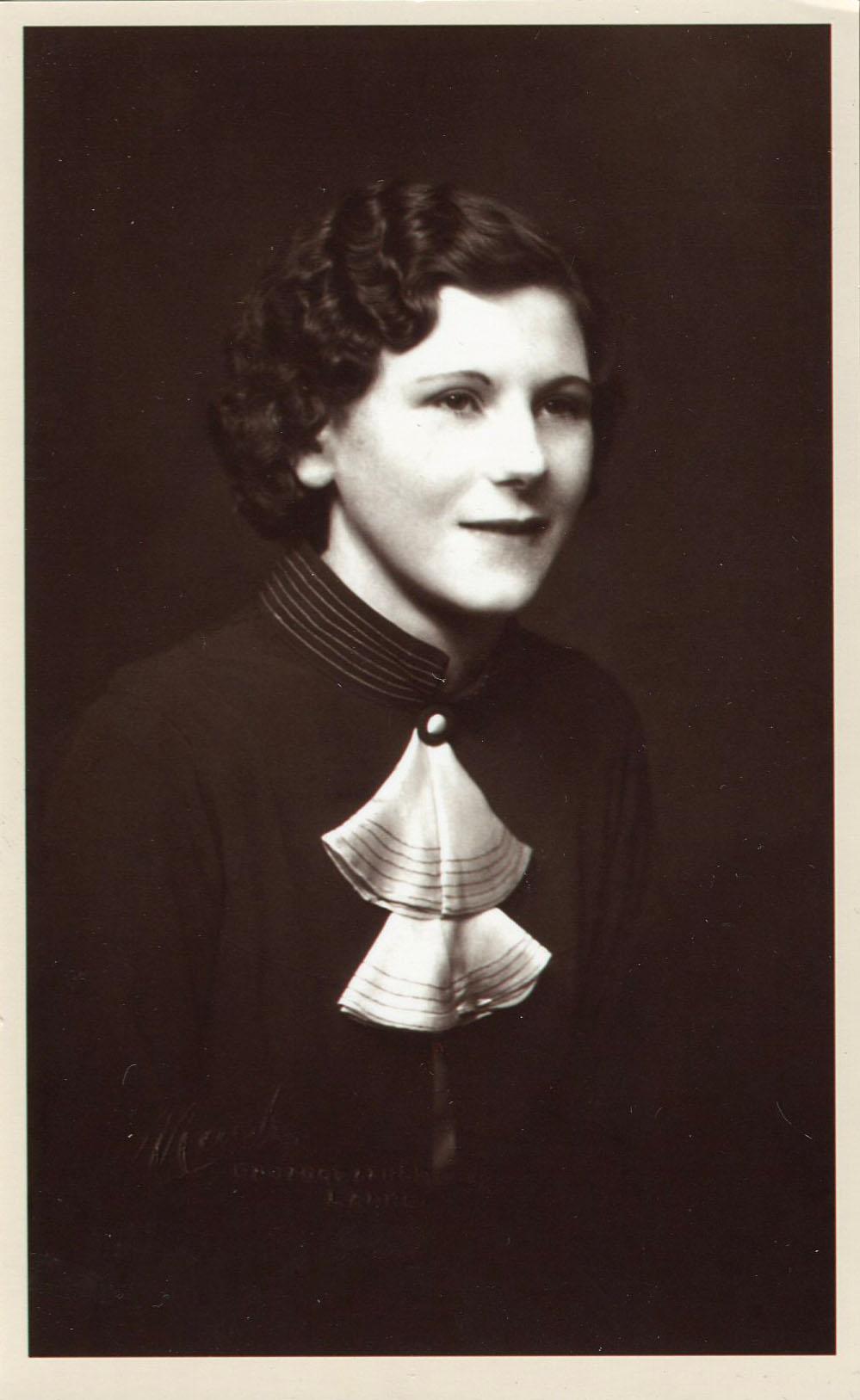

Burning corks for eyeliner by the fire Two years ago I began to do some historical research for a new novel, which to be called Waterloo Road. I was able to draw from my own experiences, having grown up with great aunts and uncles who lived on the Waterloo Road, but when Barbra Cooke got in touch to tell me about her granny Martha Doey’s diary, the novel came to life in my mind. Barbra’s aunt Irene, Martha’s daughter, invited me to her home to learn more, and during that interview, I picked up the kind of detail that could not be found in a newspaper or a history book. I discovered a world in which women scrubbed their teeth with soot from the fire, painted their eyebrows with burnt cork and went hungry as rationing stretched from one world war to the next. A picture emerged in my mind, a hazy outline of an industrial area that only half exists today, the old red brick walls of the linen mill still standing on the Lower Waterloo Road; the unbridled noise of looms, smoke belching from chimneys and the giant damn for steeping flax near present day Kent Avenue all gone. The people who congregated at the factory corner outside Billy Boyd’s store were already known to me, as I’d spent so much of my childhood at that same corner buying sweets from Duddy’s or Sally’s shop, but I began to see my old aunts and uncles more clearly. I also started to understand the significance of the 12 foot high wall that separated the kitchen houses of the Waterloo Road from the big houses where the captains and doctors resided. I discovered the world of Little Ballymena, a quarter of Larne that has since lost the moniker for which it was once known. My great grandparents were among first generation to fill the kitchen houses on the Waterloo Road, Herbert Avenue and Newington Avenue in the late 1800s. They were farming people with “Broad Scotch” accents, an eclectic mix of every Protestant denomination; religious affiliations that were often determined by whichever church was providing handouts to the poor and needy. Such folk, alongside their Catholic friends, were all united in a love of whiskey, dancing and music. Martha Taylor’s diary is buoyant with the kind of language that comes from listening and yarning. The rhythm and phrasing her words echo conversations conducted over washing lines; tales whispered in queues when ships bearing bananas came into dock and stories formed in a world in which women talked for hours. I haven't attempted to reproduce any of Martha’s diary. The following words are merely notes with my own insights of a short but rich historical resource for the novel that came to be known as Dusty Bluebells. A life of serfdom Martha, who was born in 1917, begins the diary as a small child sitting on an army blanket in the back garden of number 15 Waterloo Road. The walls are thick with snow and she is content watching the robins hop along them. She is writing in the year 2001, her mind flooded with early memories. Martha’s peace on the army blanket is shattered when she hears soldiers marching. “Tramp, tramp, tramp,” she writes. She is a small child and she is afraid. A great military parade to welcome the soldiers home after Armistice is likely to have been the occasion. Brown’s Factory area is beset with unemployment in the 1920s as the linen trade goes into decline. Men are to be found on street corners lamenting the lack of work and gravitating towards socialism. Women, who are never far from hard work, continue to scrub laundry for a pittance, tend to cut knees, cook and clean. Infant mortality rates are high: Martha’s siblings, Molly and Sammie, die within two days of each other, aged 2 and 1. The infants are remembered with much love and devotion throughout Martha’s childhood. Food is scarce, particularly meat, but fresh produce is grown in the back gardens: spuds, cabbages, scallions, lettuces, turnips, carrots, peas, vegetable marrows and strawberries. A neighbour, Jamie Reid, who has a blackcurrant bush, does a bit of poaching on the sides. Clothing is made by hand, Martha’s mother knitting jerseys and long, black stockings for the girls. Coal fuels the fires and oil lamps provide light. Martha cleans the globe and trims the the wick of the oil lamps. As yet, there is no street lighting on the Waterloo Road. The most despised man in Larne works at the Labour Exchange and is in charge of doling out money to those who are unemployed. The vocabulary of socialism is prevalent in the diary: the workmen are merely serfs; the factory owners and the authorities at the Labour Exchange their masters. These workers do not know the hand of middle class Protestant privilege. At the back of Martha’s kitchen house, the 12 ft wall encloses pigs and hens. Willie Kane occupies the end house, which has a larger yard with a hayshed and a byre for his heifers and cows. When Andy Gingles from Mill Street comes to put rings on Martha’s piglets to stop them from digging up the forecourt in the sty, the child is torn apart by the squeals of the piglets. She takes a run at Andy Gingles and kicks his shins, but this is only the beginning of Martha’s woes. She mourns the pigs’ absence when they are finally taken away. The girl next door, Emma Craig, takes Martha to Store Lane to reunite her with her beloved pigs. Martha unearths mighty squeals of pain when sees them strung up on carcasses and she returns home, still traumatised, only to walk straight into a white enamel bucket in the scullery filled with the pigs’ insides. Deafening screams follow and her da agrees that no more animals are to be brought to the house. Martha’s mother is a farmer’s daughter and an enterprising soul. The money from the sale of the piglets goes on school books, uniforms and footwear, but the promise about animals has been broken. Martha’s da comes home with a goat on a rope. It bleats all night, waking the neighbours, and has to be moved away from the backs of the Waterloo Road. Music, long walks and whiskey The Brown’s factory area is alive with music. I remember this from my own childhood in the 1980s. My uncle Dan Hewitt played all manner of instruments with his friends. Even then, it was rare to find a home on the Waterloo Road without a melodeon, fiddle, penny whistle or harmonica. Favourite tunes for Martha in the 1920s are ‘My bonnie lies over the ocean’ and ‘Blaze Away.’ Her da plays the melodeon and Martha dances to exhaustion. My own little girl, who was born in 2011, frequently asks me to sing ‘My “bunny” lies over the ocean’ before she goes to sleep. Such things are handed down. On summer evenings, loanen and braes are packed with people walking. Martha’s da takes his children up Leggs Loanen [Recreation Road] to MacNeill’s Poultry farm to see the White Leghorns, to Gibson’s farm to see the lambs and to Rainy and Hall stud farm where a great big bull races up the field. They walk onto Kirkpatrick’s Farm, which overlooks the Black Arch, round the Branch Road passing the fox’s den, Pebble Lodge and Peoples farm at Waterloo. The temperance movement is strong in the early 1900s and Reverend Boyd from St.Cedma’s, Church of Ireland, has a captive audience when he goes to the harbour to teach the evils of drink to squads from the boats, for it is well known that the workmen pile into the Olderfleet bar each evening to quench their thirst “on the slate.” Martha’s da takes the pledge and promises to never drink again, but when the Reverend Boyd sees him and Andy Dobbin “as full as the Boyne,” he names and shames them in a sermon. This is the end of the road for Martha’s da and St. Cedma’s. When his children are born, he has them all christened in the First Larne Presbyterian church. Martha’s da is an affable type, but the children know the routine when he drinks, and so they grab the spoon and knife drawer and rush to a neighbour’s house when he comes home as “full as the Baltic.” On one occasion, a chair is smashed through a ceiling and is left there dangling for the children to see. On another, Martha’s da entertains his children by juggling red, hot unders from the fire. I see a fully formed three-dimensional character in Martha’s da: he is tender when sober, but senseless when drunk, and I begin to understand why so many Presbyterian families during my own childhood condemned drink: Whiskey had been Ulster’s greatest affliction; women and children its most vulnerable victims. The Peelers scoop the drunks up off Main Street in the 1920s and they aren’t shy about about applying the boot before locking them up. Prison, known as the Black Hole or the Chooky House, is home from home for the men who battle with their temperance. The prison ship The November Hiring Fair is “black with people and animals.” Each November, folk gather around Crawford’s bar, near the town hall, where “lads and lassies for hire” make themselves known by placing a straw in their mouths. The farmer looks them over, asks a few questions and strikes a bargain, usually a shilling for six months, a deal sealed with spittle and a handshake. Some lads and lassies suffer bad masters and starve, but they are bonded to to them and there is no going back home. Martha’s brother goes missing at the hiring fair as a child and returns home, feet bleeding and filthy, with half a crown. He’d stopped at the fair on the way home from the Bridge School and earned the money for walking a farmer’s heifers to Gleno, an arduous uphill trek for a child. Billy is a stoker on the prison ship Argenta that lies in Larne Lough, and there is heartache in the mid-1920s when he goes missing at sea. Martha is at pains in her diary to explain that the men have no rights. The sailors, who carry their own food on board with them in a kit bag, are neither clothed nor fed by their employer, and the family is not compensated for the tragedy of losing Billy. On the other side of the blanket Being caught “on the other side of the blanket” is a terrible sin, a blight upon the family, so when Martha’s sister, Peggy, gets pregnant, there is a commotion at number fifteen. In a tender moment between father and daughter, Da demonstrates the makings of a great man. “While I have power in these two hands,” he says to Peggy, “you and the babe will never want.” The Newington Rangers football club [near the present day Pigeon Club] is at the centre of the community. Peggy helps out in the kitchen and walks home alone in the black, past the McGarel cemetery, the odd glimmer from a gas lamp in a window on Herbert Avenue guiding her towards the Waterloo Road. She has a job in the Brown’s factory as a “Tier-on and Drawer-in.” She is good at her job, “nimble and quick,” but when she begins to experience gastric pain, da provides the 3/6 required to send her to the doctor. Vivid colours, shapes and smells come to life for Martha as the past is reawakened in her diary: the inglenook fire, the clean bricks on the hob, the kettle on the boil, the hot drink made with powdered ginger for Peggy, the bricks wrapped in old blankets to warm her feet. There is a “merciless scream,” and Martha is sent up the road to fetch the midwife, Mrs Clover, who lives in one of the parlour houses. Mrs Clover arrives at the door with a big rubber apron on. She has been busy feeding the pigs. I think of my great granny Sarah Ross as I read the diary, as she too was a midwife on the Waterloo Road. Peggy is in labour and Martha, who is sent out of the house to take Da’s tea to work, is as “happy as a lark.” Her ma has given her a penny for the bus. She gets on it at Andy Moore’s at the corner and enjoys the novelty as the bus glides to the harbour, a rare treat. The maternity nurse, Nurse Diamond, is called upon. Peggy has mastitis and has to have both breasts lanced by a doctor. She is only sixteen. She keeps her little boy and finds a job as a cleaner, working long hours and turning her parent’s house on the Waterloo Road into a comfortable home with her earnings. There is no spending the wages “on the slate” for Peggy. She later marries Neil Hyslop, who Martha describes as “a good man.” Martha has suspicions about what happened to Peggy on Pauper’s Loanen beside McGarel cemetery, but such things are not spoken of. Lashings at the Parochial School Martha attends Larne Parochial School, a school endowed by St. Cedma’s Church of Ireland. The children are marching around the room as a teacher thumps out notes on the piano. The teacher, whose cane is an extension of his arm, grabs a child by the ears and shakes his head from side to side. Tears stream down the child’s face as he is strung up like bunny and taunted by the teacher. The victim, Martha observes in 2001, stuttered for the rest of his years. Music tuition revolves around the Larne Musical Festival, and the school is filled with cups and trophies on account of Miss Belfore’s efforts. Miss Kate Brown, meanwhile, is a pussy cat, a gentle and kind teacher who “dresses like a dream.” The children sing ‘Phil the Fluter’s Ball’ and ‘The Raggle Taggle Gypsy’ and they dress up and dramatise the songs for concerts. In fifth standard, Martha has to tell Miss Britten that she cannot say the Church of Ireland creed. “I belong to the Reverend John Lyle,” she says. Sally Ross, sister of my granny Jemima, is a friend of Martha’s. She likewise cannot say the creed as she belongs to “the Covenanters at the Harbour.” Martha is sent away at the age of eleven to clean for a relative. She is far from home for six whole weeks and shudders at the thoughts of using the dry toilets in Ballyclare. She skips school and falls behind in maths. A question comes up in class when she returns. A room measures so many feet high and so many feet wide. How many wallpaper rolls would it take to paper the room? Martha tries to work it out, but she calculates one roll of wallpaper too many. The teacher goes for her. He tucks her arm under his elbow and he whips each of her hands six times. She sobs until she has no breath left. She plunges her lashed hands into cold water, but the blue welts are already rising and the blood is gushing from her. She faints and slips to the ground, but is told to sit up straight on the chair by a teacher whose face is “screwed up with venom.” Martha’s sister, Peggy, arrives at the school the next day “dressed to kill,” her knee boots laced up below her navy blue nap coat, her collar out over the coat lapels, a red jockey cap on her head. “I’ve come about my sister Martha,” she states. “She is a very delicate child. You sent her home yesterday with a pair of hands you wouldn’t see on a navvy.” Peggy pokes the teacher on the chest. “If this ever happens again, it won’t be your hands I’ll be going for, it’ll be your face, and I’ll knock your nose right of it.” ‘The oul blirt’ I find myself saying, as I read Martha’s diary, almost in tears at Martha’s plight. Children are the real serfs of 1920s Ulster. “So what if I never learned the sum!” Martha contemplates with wit in 2001, when she has more than 80 years of mathematical experience behind her. “At 1 shilling per roll of wallpaper,” she writes, “the extra roll would have come in handy for backing school books.” The short diary ends and I’m lost. I want more, but I have what I need for my novel and I create two women with a childhood like Martha’s, one who stays on the Waterloo Road and one who moves to the other side of the wall. About Martha Taylor (Information provided by Martha’s granddaughter, Barbra Cooke) Martha Taylor was born on 5th August 1917 and was reared on the Upper Waterloo Road. Her mother was Margaret Owens, whose people had originally come from Wales in the late 1690s. Owenstown, a townland near Ballysnod and Gleno, is named after them, and the family has a copy of the extensive family tree demonstrating the links. Margaret Owens was a hard worker, who knitted, sewed and took in washing from neighbours to subsidise the family income. Her father was William Taylor from Rory's Glen in Kilwaughter, not far from Owenstown. He was an interesting character who wrote poetry and who travelled to Australia to look for his brother without telling his wife. He was practically destitute, but miraculously got his passage back home, with the help of a fellow Larne man. Martha only had a primary school education and her first job was in the weft office at Brown's factory. She met and married William Robert Doey (born 25th September 1912), who lived on the Mill Brae in Larne. He was an electrician, who served his time with Willie Law. They had four children, Jean (Barbra’s mother), Irene, Bobby and Margaret. They were a close and happy couple, but Robert died very suddenly from a massive coronary on the 3rd September 1975 at the age of 62. When her children were young, Martha worked for a short time at the Bleach Green's Sun Laundry on the Bank Road [Rea's of Larne is currently located there.] Later, when the children were grown, she worked in Standards Telephone and Cable company full-time. She never returned to work after her husband died; his death was a huge blow to her. Martha loved reading and educating herself and was often found in Larne library. She was a member of the historical society and wrote a few articles for the Corran magazine. She was also a keen bowler at Larne Tennis and Bowling club. Poetry was her passion, whilst her local knowledge was such that people would often consult her for information. She often said that living on Kent Avenue was much more entertaining than Coronation Street. Protestants and Catholics lived and worked together there and helped each other through good times and bad. Martha, the matriarch of the family, was much loved, and when she died on the 11th October 2005, it was a big loss to her family, old and young alike. Dusty Bluebells "Pithy with Ulster Scots, old rhymes, cures and sayings, there is a sense of magic to it all. A book to warm your heart on a cold winter’s night." The Irish Times Angeline King is the author of: Irish Dancing: The festival story A history of dancing in Ulster with a focus on the festival tradition of Irish Dancing. Click here to buy. Snugville Street "An enjoyable coming-of-age tale with a Belfast twist" (The Irish Times) Click here to buy A Belfast Tale “Uniquely, authentically and enjoyably Belfast" (Tony Macaulay, author of Paperboy.) Click here to buy. Children of Latharna Lyrical and nostalgic; wistful and humorous, Ian Andrew, author. Click here to start reading.

2 Comments

Alan McClean

29/6/2019 17:04:15

You would probably enjoy a chat with my dad. Born into Waterloo.Road in the 1930s, and full of stories about people and happenings there. The war years as a child, bomb shelters, how life was lived. Then the individual stories like a child getting injured by shrapnel from a bullet someone threw on a fire, or the day Laurel and Hardy passed through Lower Waterloo Road on their way to the coast.

Reply

Angeline King

22/3/2021 18:38:34

Alan, sorry I'm only seeing your comment now! I love that Laurel and Hardy story! :)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

ProseHistory & folkloreJean Park of Ballygally

Fiddles and Melodeons Martha Taylor's diary Jean McCullagh at 104 Ballymena & the McConnells Arms in Irish Dancing Catholics & Protestants in Irish dancing Dancing in Victorian Ulster Essays

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed