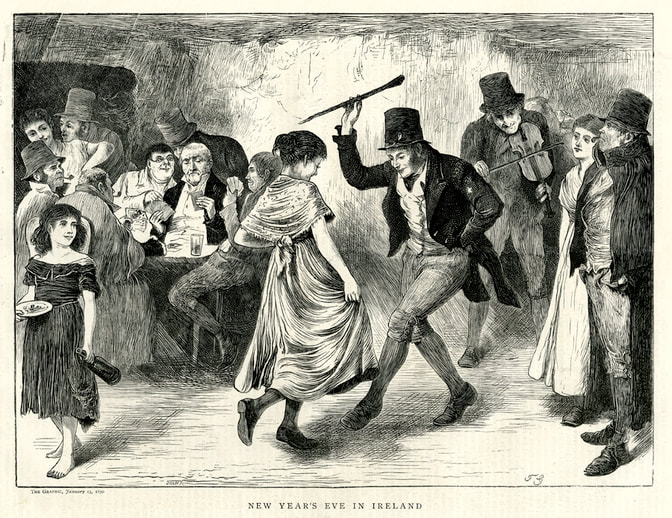

How did did our ancestors, the young and old of nineteenth century Ulster, foot it to the dance floor? The answer, if you're partial to Victorian literature, can be found in a recently republished novel called Orange Lily. May Crommelin’s novel, set in County Down in the 1870s, is well worth a read, but what caught my attention, as I made the last touches to my book on the history of Irish dancing, was the description of dancing, and in particular, the reference to Soldier's Joy, my 6 year-old daughter's favourite team dance. No slithery-slathery walzes! ‘Soldier’s Joy' is a popular team (country) dance in the festival tradition of Irish dancing, and the dance is a charming spectacle to behold as the children knock, knock, knock, clap clap clap and rolly polly polly to the music. However, in Orange Lily, the dance is a little more rustic. ‘Big Gilhourn,’ an affable farmer, who has taken a fancy to Orange Lily despite her unerring love for Tom, takes to the earthen floor of the barn like Michael Flatley, rejecting any notion of lilting to a modern dance: “None of your new slithery-slathery walzes for me. What I like best is to see a man get up and take the middle of the floor - and foot it there for a good hour!’ ‘The Soldier’s Joy’ for me, if I may make so bold as to ask that request.” Quadrille The 'Soldier’s Joy' in this sense is a quadrille, a square dance and the mainstay of country dancing throughout the whole of Ireland for most of the 1800s. The quadrille was danced at speed and with great energy. Indeed, by the 1870s, there were complaints from the countryside that new dances like polkas and waltzes were too slow and repetitive for the Irish, lacking as they were in rich steps of yore. ‘Stepping’ “Stepping” was a feature of the old social dances. Today, céilí dances of the feis tradition of Irish dancing and team (country) dances of the festival Irish dancing tradition, are mainly composed of side steps and the promenade step, but in the late 1700s and early 1800s, social dances were rich in complex steps inherited from French dance masters. It would have been common to see ‘heels and toes,’ ‘drumming’ and ‘cuts’ within the social dance. This, in turn, meant that many country dancers could perform solo performances, based on the few steps they had either picked up or learned in a formal setting. In the novel, Orange Lily, it is notable that “Big John executed a bit of a breakdown by himself with much applause.” Steps v Grace Stepping, however, had gone out of fashion by the 1870s, so much so that the grandfather and grandmother among those present at this "Orange ball" ( a barn dance) in Orange Lily were the envy of their “degenerate descendants” because they knew the best steps. By the time the white collared men of the Gaelic League had set upon the idea of reviving traditional dancing in the early 1900s, the fashion was for a more elongated step, and a great tug of war between steps and grace commenced that was to last well into the 1930s, when finally, grace triumphed in gold medals at musical festivals and feiseanna. The reel in Orange Lily is described as “vigorous.” Big John takes the floor in his hobnail boots in the manner of a River Dance star, a reminder that the men of Ulster were once slightly more partial to dancing than they are today. Big John is described as follows: “Big John did his steps with a nimbleness wonderful in such a heavy-looking man, finishing up every now and then with a solid pounding that made delicate-nerved folk like his cousin Daniel think it a “puffect mercy that he was on an earth-floor, in which holes were cheaply mended.” (A/The) Soldier's Joy In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Lambeg Irish folk dancing society, a group of middle class professionals influenced by the European folk dancing revival, travelled around Ulster alongside Peadar O’Rafferty, a Gaelic League feis champion dancer, collecting and recording traditional folk dances that were still alive in the countryside. ‘A Soldier’s Joy,’ was one of those dances and more than one hundred years after its introduction to Ireland, it was recorded in Mr Peadar O’Rafferty’s Irish Folk Dance book of 1934. That the dance can still be seen at Irish dancing festivals today is due to respect for tradition among the Irish dance teachers of today, the dedication of the festival Irish dance teachers of the twentieth century like Patricia Mulholland, Sadie Bell and Marjorie Gardiner, and to the folk dance revivalists of the 1920s. Angeline King is the author of:

Irish Dancing: The festival story A history of dancing in Ulster with a focus on the festival tradition of Irish Dancing. Snugville Street "An enjoyable coming-of-age tale with a Belfast twist" (The Irish Times) Click here to start reading. A Belfast Tale: “Uniquely, authentically and enjoyably Belfast" (Tony Macaulay, author of Paperboy.) Click here to start reading Children of Latharna: Lyrical and nostalgic; wistful and humorous, Ian Andrew, author Click here to read for free

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ProseHistory & folkloreJean Park of Ballygally

Fiddles and Melodeons Martha Taylor's diary Jean McCullagh at 104 Ballymena & the McConnells Arms in Irish Dancing Catholics & Protestants in Irish dancing Dancing in Victorian Ulster Essays

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed