|

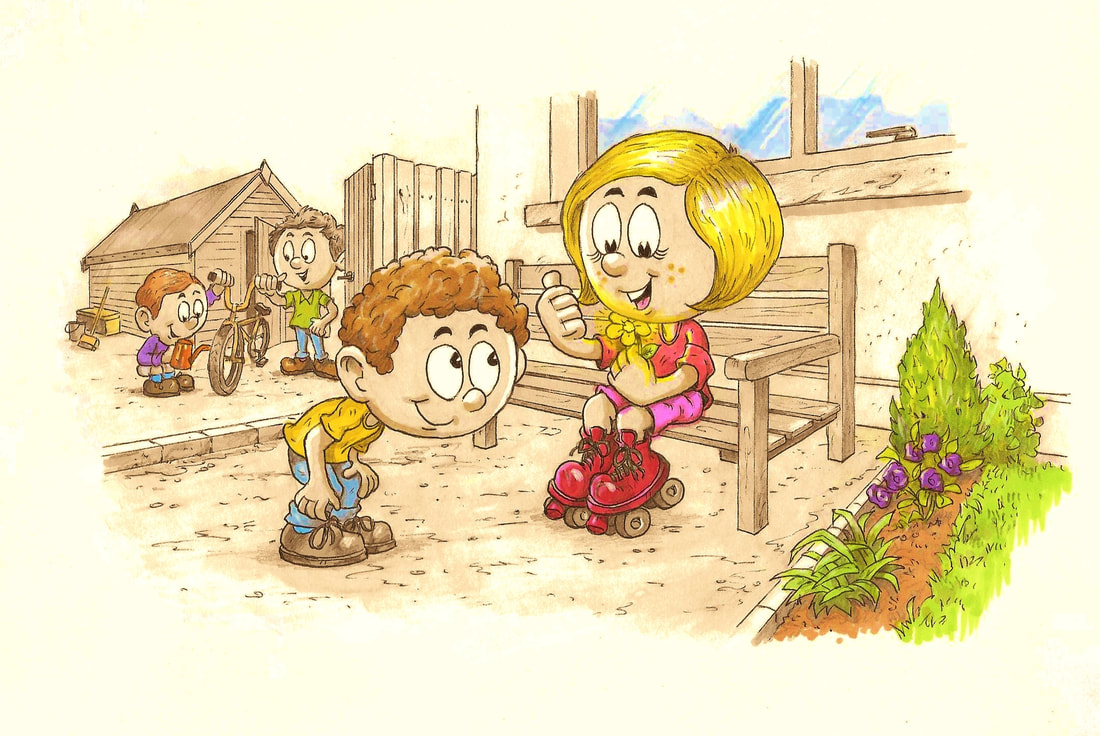

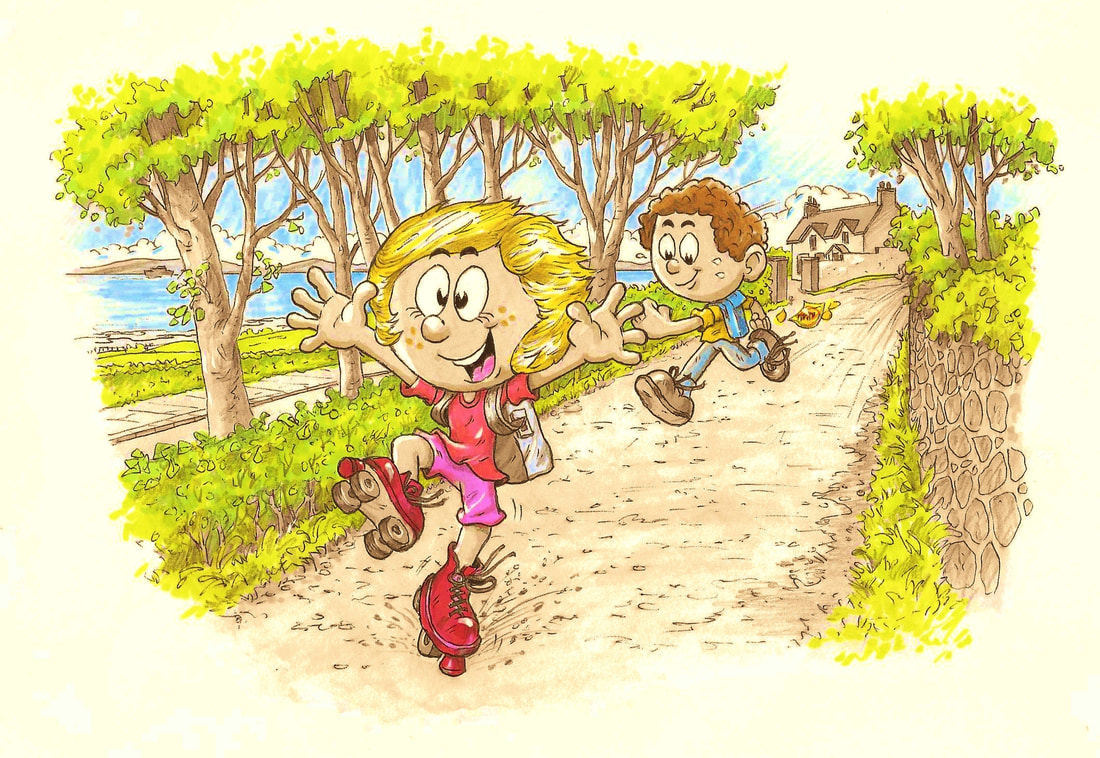

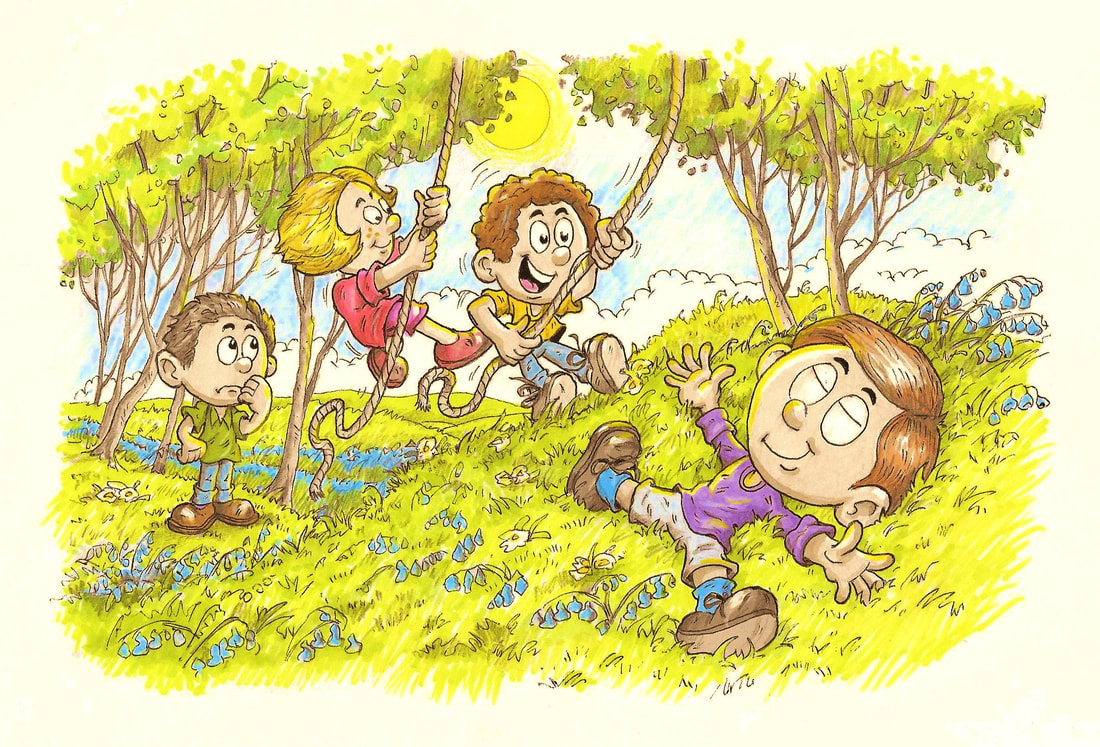

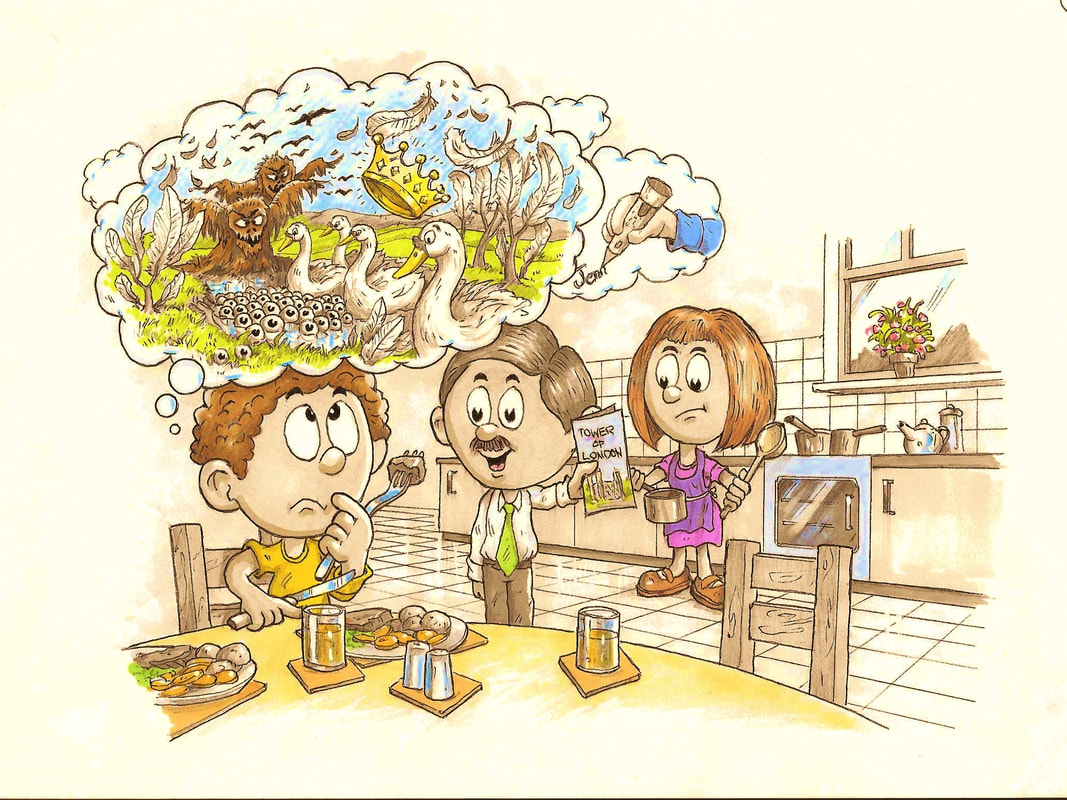

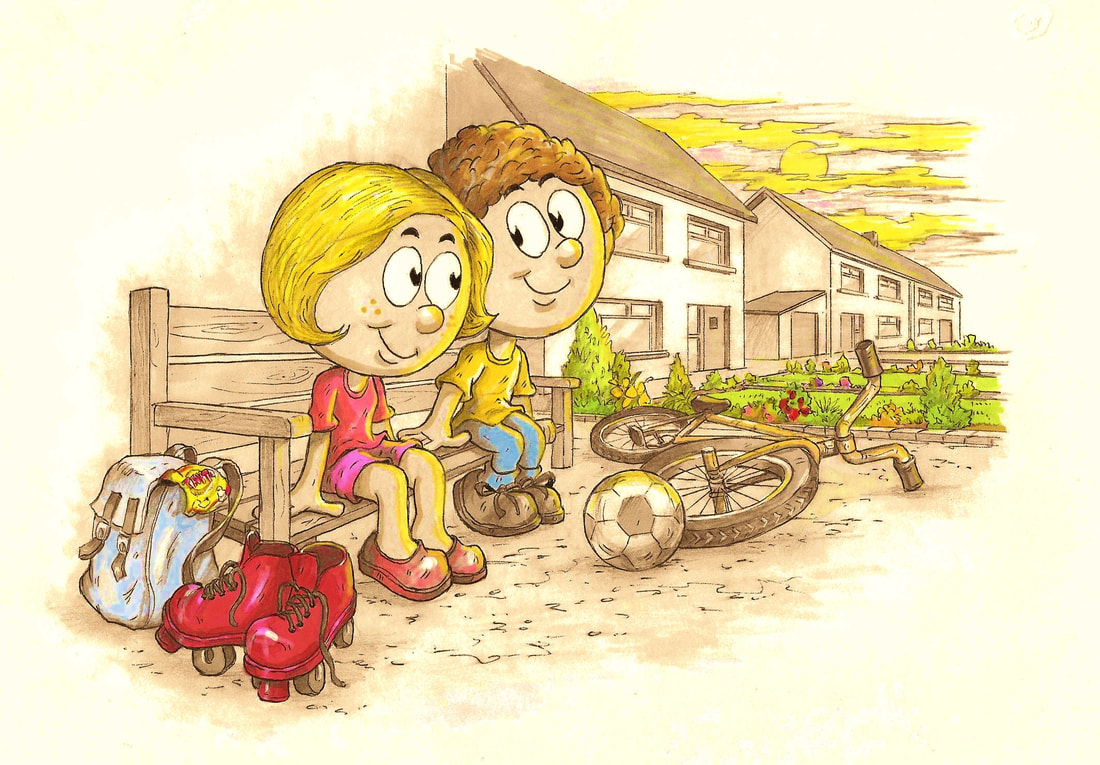

I was sick, sore and tired of the games that Harry and Gary played. I was sick, sore and tired of BMXing, I was sick, sore and tired of the A-Team, I was sick, sore and tired of the band stick and I was sick, sore and tired of football. ‘I’m bored.’ I said to my mammy. ‘How could you be bored? It’s summer. You’re off school. The street’s full of weans. Away out and play like the rest of them.’ ‘They only want to play on bikes and all. I’m bored of bikes and all.’ ‘Jenny’s on her own over there. Away and play with Jenny.’ My mammy’s eyebrows were curved like question marks and she had a semicolon smile. She knew that I was not sick, sore and tired of Gary’s sister, Jenny. Jenny goes to the Andrews’ school of dancing at the Town Hall. Each Saturday, I’m there alone on the boy’s side of the hall. Jenny is there on the other side surrounded by thirty girls. It’s wile hard to be alone at dancing without stories birling through my mind. I do the three-hand reel with the girls. There’s a jellyfish of a girl on my left with arms and legs that wriggle in all the wrong directions. There’s a swan of a girl on my right with strong arms and graceful legs. The swan girl is Jenny. ‘Well, what are ye going to do?’ my mammy asked. ‘I dinnae know,’ I replied. ‘Ye dinnae know?’ she said. ‘What about a game that you like?’ ‘Harry and Gary won’t like my games.’ ‘How do you know they won’t like your games?’ ‘I just know.’ ‘Well, this might be your last summer with them, so you should try to play together.’ ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Nothing.’ Mammy had a great gleek of worry on her face. ‘It’s just that you won’t be at St. Joseph’s with Harry anymore and you won’t see much of Gary once you all go to different schools.’ It was true that we were all going to different secondary schools, but school didn’t matter because we all played together on Greenland Grove. ‘Away and play with Jenny.’ ‘Harry and Gary say that I’m a right Jinny if I play with girls.’ ‘Och, a lot of nonsense! Never listen to Harry and Gary!’ I walked across the road. Gary’s house is right opposite mine. We occupy prime sentry positions on Greenland Grove. As soldiers of fortune, Gary said it is our duty to protect the street from any trouble. Jenny was on the summer seat at the front of her house, her legs pinned to the ground with the stoppers of two red roller boots. ‘They’re around the back,’ she said. She was twirling a butter cup in her hand. She placed it under her chin and it changed her neck to the colour of sunshine. Jenny’s face is all dotted with freckles and she has a blond bob that hides her periwinkle ears. Her eyes were twinkling under the buttercup. ‘You must like butter,’ I said, and Jenny looked up and smiled. I went around the back and watched Harry and Gary oil the chains on their bikes. ‘I’m fed up with BMXing,’ I said. Gary’s eyes were quare and wide with suspicion. ‘Well, what do you want to do then?’ he said. ‘I dinnae know,’ I said. ‘What about King Billy ramps?’ Gary said. Gary was mad about King Billy. If he wasn’t making us all cycle across a pretend Boyne River on bikes, he was leading us around Greenland Crescent in a dummy flute band. ‘I’m bored being King Billy,’ I said as a flash of red rolled down the driveway. ‘What about King Lir? Can we have a game of King Lir for a change?’ I dinnae know King Lir,’ said Gary. ‘Do you know King Lir, Harry?’ ‘No,’ said Harry. There was only one problem with playing King Lir, and I knew that my friends wouldnae like it. ‘We’ll need a girl!’ I said. ‘Och no!’ Harry and Gary rhymed. ‘Not a girl!’ ‘King Lir had three sons and a daughter, so we cannae play King Lir without a daughter. It would be like playing King Billy without King Jimmy.’ Alright then,’ said Gary. ‘Jenny can play, but if it’s a load of ould rubbish, you’ll no get to pick the game again.’ I wasnae too convinced of the game myself. I was about to suggest something else when my eyes cowped and fell on the reflectors of Jenny’s roller boots. It would be nice to spend the day with Jenny, I thought. It’s wile hard to think of a girl like Jenny without stories birling through my mind. It was time to go. Harry and Gary were on their bikes, Jenny had her roller boots slung over her shoulders and I had a rucksack with half a plain loaf and Tayto cheese and onion crisps for crisp sandwiches by the shore. ‘Let’s go then,’ I said as I led my gang through the backs of Greenland Crescent and across the GEC factory playing fields. I wondered how I was going to explain to Harry and Gary that they were about to be transformed into feathery swans. I was sure that Harry and Gary wouldnae like the idea of being transformed into feathery swans. The clouds were raining droplets of sun on my face. It’s wile hard to feel droplets of sun on my face without stories birling through my mind. ‘Once upon a time,’ I began, as we reached the Recreation Road. ‘Is this some kind of fairy tale?’ It was Harry and his voice was brave and troubled. ‘Shush and listen,’ I said. ‘A long time ago, there lived a king. He was a gentle and a kind king and he loved his four children. The eldest child was called Fionnuala and she was said to be the finest cailín in the land.’ Harry and Gary were half listening as they mounted their bikes, but I looked at Jenny with her freckled face and pale skin and she was all periwinkle ears and twinkling eyes. ‘King Lir’s wife died and he married a lady called Aoife,’ I continued. ‘Aoife was his wife’s sister and she was only concerned with fame and fortune. She despised her niece and three nephews.’ Jenny stopped to attach her roller boots to her feet. I’m listening,’ she said, ‘but I’m going to skate down the brae. Save the rest of the story for when we get to the bottom.’ Skate down the brae, I thought. Jenny can’t skate down the brae, I thought. The Waterloo Road sloped right down onto the Coast Road on a blind bend. Harry and Gary were ahead and out of sight. What was I going to do? I’d seen Jenny on her roller boots. She was good on the flat of Greenland Grove, but one time I saw her skate down Greenland Crescent, and she took a wile tumble at number three. There we were at the top of the Waterloo Road; me on the precipice of my reputation; Jenny on the precipice of her life, and the roller boots were moving and crunching gravel on the brae. Jenny was rolling fast. I couldnae run fast, but I was running at a pace so swift that I could have won the school sport’s day prize for sprinting instead of coming last. Jenny was scraiching and screaming and there was only one thing I could do. I reached out my hand and I snatched Jenny’s hand in my own. I looked around. There was no one nearby. I was holding Jenny’s hand with no three-hand-reel between us. It’s wile hard to hold Jenny’s hand without stories birling through my mind. I let go and prayed that Harry had not seen me holding his wee sister’s hand. The Chaine Memorial Park is lush. From the top of the park, the purple-green outline of Scotland can be seen where the land wraps up the sky. From the middle of the park, the Townsend Thoresen can be seen cutting a triangle of white foam where the sea and sky unfold. From the bottom of the park, a white pebbly shore can be seen where the land wraps up the sea. I sat in the copper-topped shelter in silence while Jenny changed back into her shoes, and I looked at the rippling bumps and mounds and drumlins of the park. My eyes travelled down the winding paths, beyond the fish pond and onto the shore. It’s wile hard to sit in silence in a copper-topped shelter without stories birling through my mind. ‘There they are!’ said Jenny. ‘They’re playing army assault courses.’ Army assault courses, I thought. Not army assault courses, I thought. I was sick, sore and tired of army assault courses. I followed Jenny to the Billy Goats Gruff wooden play park. There they were, Harry and Gary, bounding over the wooden beams with their feet, grappling along the monkey bars with their hands and slinking underneath the Billy Goats Gruff bridge on their bellies. There are no goats trip-trapping over wooden bridges when Harry and Gary are at the Chaine Memorial Park. They sped away from the bridge and scrambled up the cliff. I waited by the Billy Goats Gruff bridge as Jenny trip-trapped over the wobbly wood. ‘Right, then, Billy, show us this King Lir game,’ Harry shouted from the bottom of the hill. He was clarried in clábar to the knees. ‘Well, I said,’ as I walked across the promenade to the white railing by the sea. ‘King Lir’s new wife took the four children down to a lake for a swim.’ ‘Brilliant!’ shouted Harry, who had crept under the railing onto the white, pebbly shore. He was already kicking off his shoes. Gary and Jenny followed behind, and I slid under the white railing. I removed my shoes and socks and tiptoed over the pebbles. I skipped over the limpets that were glued to the rocks. I scuttled across the sand as slimy seaweed twisted around my toes. I dipped my feet in the rock pools to test the water. The salty, cold water stung the BMX cuts on my knees. ‘It’s cowl! It’s cowl! It’s cowl!’ gasped Jenny. ‘Och, stop being such a chicken,’ said Harry. Jenny was fleeing from the water and Harry was shouting, ‘Buck buck buck buck!’ ‘I don’t care,’ said Jenny. ‘It’s cowl!’ It was cowl and I was foundered, but the wind was right and breezy through my hair, and the water was right and sprightly on my skin. It was a nice feeling sitting there in the shallow water sieving the cockles and pebbles with my fingers and toes. It’s wile hard to sieve cockles and pebbles with my fingers and toes without stories birling through my mind. Harry and Gary were laughing and splashing in the sea. I felt right and sorry for Jenny who was all alone on a rock. I climbed up beside her. She had goose pimples on her arms that were so red and swollen, that I wondered if feathers would sprout from her skin. ‘King Lir’s wife cast a spell on the four children,’ I said. ‘She watched from the shore with a wicked smile as they each grew feathers. The children didnae know what was happening to them. They didnae know that Aoife had turned them all into swans.’ Harry and Gary disappeared underneath the water. They weren’t interested in King Lir. They just wanted to swim in the mort cowl water. ‘The swans were banished from their land for nine hundred years.’ I looked out across an expanse of low tide towards the pencil shape of the Chaine Memorial Tower. I imagined lifting the Chaine Memorial Tower and writing a story just for Jenny. Jenny was all periwinkle ears and twinkling eyes. ‘For three hundred years, the swans were set adrift in the wild and solitary sea of the Moyle.’ I could feel a wind on my back. ‘Boo!’ came the voice of Gary and up went the arms of Jenny as she let out a scraich that could have turned the tide. Standing behind us on a black, basalt rock were two sea monsters draped in slimy, brown seaweed. Jenny began to cry and I looked at Harry and Gary and shook my head. Gary was the first to peel back his seaweed. ‘Ha ha! Gotcha!’ he said. ‘Don’t be such a girl,’ Gary said to Jenny. ‘I am a girl,’ Jenny said to Harry. ‘Well don’t be such a Jinny,’ Gary said to Jenny. ‘I am a Jenny,’ Jenny said to Gary. ‘King Lir’s no a bad game,’ smiled Gary, who shook off water from his skin like a duck. His T-shirt and shorts were wringing right through. ‘Three hundred years at the Moyle is a wile long time, though. I dinnae fancy three hundred years of school!’ he added. ‘Not the Moyle school,’ I said. I pointed to the north where the tip of Ireland noses the tip of Scotland at the Mull of Kintyre. ‘That’s the Moyle sea,’ I said, ‘but on their route north, the swans stopped here in Larne in the ancient kingdom of Latharna. They were welcomed by the land. It saw that they were cold and it reached out its arm to them to protect them from the wild sea. The arm is called Islandmagee and it sheltered them as they rested.’ ‘See you in the forest!’ Harry shouted as he and Gary sped off on their bikes, dripping seaweed and water behind them. I ran alongside Jenny. We were in Bluebell forest, a sparse wood with a scattering of spindly trees. Two ropes dangled from branches and we took it in turns at swinging like Tarzan. When the sun skinkled through the branches, we lay side by side on a grassy clearing to dry out our shorts. It’s wile hard to see the sun skinkling through the branches without stories birling through my mind. ‘What happened to the swans?’ Jenny asked, gleeking up over the square fringe on her face as she propped her head on her elbow. ‘Princess Fionnuala looked after her brothers for three hundred years at the Moyle sea. The swans then had to move back west where they spent another three hundred years swimming in a lake, but they enjoyed their time here. When they flew over the ancient land of Latharna, their long, white feathers floated to this very spot and transformed into spindly trees.’ Jenny’s blue eyes were sad. I sat up to face her as the story birled through my mind. ‘They shed tears so heavy that they cascaded into a river, a river called Inbhear an Latharna.’ Harry and Gary were listening too. ‘What’s up next?’ said Gary, as a crow squawked in the trees. It’s wile hard to hear a crow squawking in the trees without stories birling through my mind. ‘Next up is the Pond of Eyes,’ I smiled. I led our gang back along the cliffs to the Chaine Park. We climbed the rippling bumps and mounds and drumlins until we reached the pond. Harry and Gary were listening and I was heart- glad of the story in my head. ‘When the four swans arrived here, the guillemots flew in from Stranraer in Scotland and welcomed them. The kittiwakes flew in from the Gobbins and welcomed them. The buzzards flew down from the Glens and welcomed them.’ My hand was soaring through the sky. ‘But Queen Aoife was a wicked Queen and she sent crows from the other side of Ireland to count the swans during their time at the Moyle sea. The crows carried her cruelty and they cast cold winds over the swans as they bathed in the warmth of Larne Lough. The might of the guillemots and the kittiwakes and the buzzards held back their winds and Larne Lough kept King Lir’s children warm. When the Queen died, the land of Latharna reached out its hand and snatched the eyes from all the crows and wapped them into this pond. Today the crows can still be heard squealing in pain as they circle the sky.’ Harry and Gary were all periwinkle ears and twinkling eyes, and they leaned in close to me as we all bent over the pond. I smiled at Jenny and immersed my hands in the green water, slathering frog spawn over my arms. In a swift movement, I held up a dripping hand of crows’ eyes close to the gleeking eyes of Harry. ‘That’s minging,’ he said, yeuching and laughing as he too slavered his hands in the cool gundge. ‘You’re right and good at telling stories,’ said Gary later that day as we walked from the corner shop at Boyne Square with our drinks. A flutter tingled my throat. ‘Ay, I think you’re the best person at telling stories in the world,’ said Harry. The flutter travelled into my tummy. I liked the bit about the trees,’ said Jenny. The flutter was all over my legs and I smiled as I sipped pride through the straw of my strawberry Tip Top. It’s wile hard to drink pride through the straw of my strawberry Tip Top without stories birling through my mind. My daddy was quiet at dinner. My mammy was gye and quiet too. I wanted to tell them both about my King Lir story. I wanted to tell them about the monsters coming out of the sea and I wanted to tell them about the Pond of Eyes. I wanted to tell them everything, but before I could begin my story, my daddy said, ‘How would you feel about moving to England? The world stopped moving and the stories stopped birling through my mind. ‘We’re thinking of moving.’ It was my daddy’s voice again and my mammy was looking at me and then at him with a great gleek of worry. It would be good. There’d be no trouble there. You’d like it.’ Trouble! I thought. What trouble was there here? I thought. It was all BMXs. It was all band sticks and football and storytelling by the shore. It was all Harry and Gary, the soldiers of fortune of the swans of King Lir. It was all Jenny. It was all Jenny with her periwinkle ears and twinkling eyes. ‘You’d go to a nice school in London. Your daddy will have a job in the Metropolitan Police in London and there’ll be no trouble,’ she continued. ‘There is no trouble!’ I shot. Colour dreeped from my mammy’s face. ‘You’ll like it, son,’ said my daddy. I stood up. ‘I am not going to live anywhere. I am staying here.’ I was crying on the inside, but I could still taste the pride that I’d sipped on the way home from the shore and I didn’t want to let it go. I slammed the kitchen door and walked outside. Harry’s ball was lying in his driveway. I kicked it between the two jumpers and scored. Harry’s bike was lying on its side in the garden. I lifted it and I rode down the street. I assembled the ramp that was on the footpath at the corner of Greenland Grove. I wheelied Harry’s BMX bike and I circled the wide part of the Grove. I accelerated and I sailed over the ramp, and the tears that were hiding inside of me dried and I was heart-feard. I was heart-feard leaving Greenland Grove. I packed the ramp away and took Harry’s bike back to his driveway. Jenny was there on the summer seat. I sat beside Jenny. She was all quiet ears and still eyes. ‘Is it true?’ asked Jenny. ‘What?’ I replied. ‘Your mammy told my mammy today that you might be moving to England.’ I didn’t want Jenny to see that I was heart-feard of leaving Greenland Grove. I tipped my head up to the sky. Greenland Grove is all yellow in summer evenings, like someone is holding a giant buttercup against the rows of white pebble-dash. I looked over at my house on the corner, the gateway to the soldiers of fortune. I looked up to the box room where I had served five years of sentry duty alongside Harry and Gary, watching the street for trouble, checking under cars for bombs. Nothing had ever happened. There had never been any trouble on Greenland Grove. And it had been a long time since there was trouble in the land of Latharna. ‘I don’t want to go to England,’ I said. ‘There’s no trouble in England,’ Jenny said. ‘There’s no trouble here,’ I said. ‘There’s a tower of London in London,’ she said. ‘There’s the Chaine Memorial Tower in Larne,’ I said. ‘There’s Princess Diana in London,’ she said. ‘There’s Princess Fionnuala here,’ I said. Jenny smiled. I smiled. I pushed Jenny with my shoulder. Jenny pushed me with her shoulder. I sat with Jenny. She said nothing and I said nothing, and we watched the children in Greenland Grove play under a buttercup sunset. I felt heart-glad to be sitting beside Jenny and heart-feared to ever have to say goodbye. She was my best friend and I knew that I would never be sick, sore and tired of Greenland Grove again. I hope you enjoyed this story, the third of three stories published in the book 'Children of Latharna.' If you would like to find out how to order the book for individuals or for schools, please contact me directly by email. If you are in Belfast, you can pick a copy up at the Discover Ulster Scots Centre (RRP £10.00)

Angeline King is the author of: Irish Dancing: The festival story A history of dancing in Ulster with a focus on the festival tradition of Irish Dancing. Suitable age: This is a history book, recommended for secondary school pupils and adults. Click here to start reading Snugville Street "An enjoyable coming-of-age tale with a Belfast twist" (The Irish Times) Suitable age: This novel is to be enjoyed by adults. Click here to start reading A Belfast Tale “Uniquely, authentically and enjoyably Belfast" (Tony Macaulay, author of Paperboy.) Suitable age: This novel is to be enjoyed by adults. Click here to start reading Children of Latharna Lyrical and nostalgic; wistful and humorous, Ian Andrew, author. Suitable age: These stories can be enjoyed by "big weans and wee weans." Click here to start reading. The Piper of Black Cave The legend of the piper of Black Cave in Larne. Why is his music so sad? Why is his music so flawless? Suitable age: This story is illustrated for children but can be enjoyed by adults too! Click here to start reading.

1 Comment

1/4/2023 14:17:26

I agree that it’s essential to be genuine and contribute to the discussion to get the most out of blog commenting.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |